forecast horizons. JOCCI ranked first

at the 3-month and 6-month horizons,

and SMPS took the lead at the 12-

month horizon. Although CRB did

better than the no-indicator model in

the short run, its forecasting ability

deteriorated at longer forecast hori-

zons. The results in figure 2 seem to

indicate that JOCCI and SMPS im-

proved the performance of the fore-

casting model, since they succeeded

in lowering the average forecast error.

However, the differences between the

forecast errors of the no-indicator

model and the forecast errors of the

indicator models were very small,

averaging less than one-tenth of a

percentage point. Such a small im-

provement in the forecast error seems

insignificant when we consider that

between January 1970 and June 1994

the annual inflation rate ranged from

approximately 2% to over 12%. As

figure 2 shows, we also calculated

significance levels to measure the

probability that the mean of the dif-

ferences of the squared forecast er-

rors was actually zero. Values above

0.05 indicate that the average differ-

ences between the forecast errors

were so small that they are likely to be

truly zero in the long run and hence

insignificant. Conversely, values be-

low 0.05 indicate that we can reject

the hypothesis that the mean of the

differences is zero. In the latter case,

we would consider the improvement

in the forecast significant. Only the

SMPS model reduced the forecast

error by any statistically significant

amount, and then only at the 12-

month horizon.

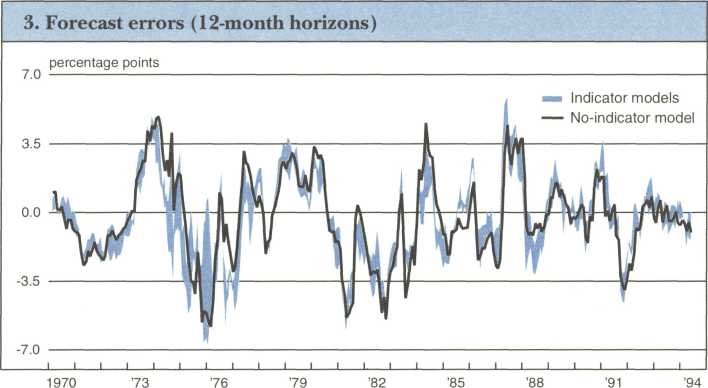

Figure 3 allows a visual check of how

similar the forecast errors from the

various models truly are over time.

The chart depicts the difference be-

tween actual inflation and forecasts of

inflation at 12-month horizons (fore-

cast errors) produced by the no-indi-

cator and indicator models from Janu-

ary 1970 to June 1994. It is clear that

with only a few minor exceptions, the

path of forecast errors from the three

indicator models (depicted by the

shaded band in the figure) is almost

identical to the path of forecast errors

from the no-indicator model. This

shows that the difference between the

forecast errors tends to average zero

over the time period. It also shows

that the size of the forecast errors

from all of the models is very similar.

Clearly, commodity-based indicators

appear to add no valuable informa-

tion to that already provided by past

inflation.

Conclusion

Economic indicators have value only

to the extent that they possess unique

and independent information. In

addition, they can be useful forecast-

ing tools if they reliably and consis-

tently satisfy the purpose for which

they were designed. The three com-

modity price indexes we analyzed

were all created to measure anticipat-

ed inflation. Yet our findings show

that they don’t do any better than the

past history of prices. That is, even

though CRB, JOCCI, and SMPS con-

tain some qualitative information on

price movements, they possess no

unique information for measuring

changes in inflation. Although these

indexes fail in their role as forecasters

of inflation, they still provide valuable

real-time information on aggregate

price movements. The task of the

sophisticated analyst is to interpret

these movements carefully in light of

the compositional problems that char-

acterize commodity-based indicators.

—Francesca Eugeni and

Joel Krueger

1Francesca Eugeni, Charles Evans, and

Steven Strongin, “Commodity-based indica-

tors: Separating the wheat from the chaff,”

Chicago Fed Letter, No. 75, November 1993.

2The Commodity Research Bureau Futures

Price Index (1967=100) is compiled by the

Commodity Research Bureau, Inc., Chica-

go. TheJournal of Commerce Industrial

Price Index (1980=100) is compiled by the

Center for International Business Cycle

Research at Columbia University, New

York. The Change in Sensitive Materials

Prices (1987=100) is calculated as the

moving average of the monthly changes in

the Index of Sensitive Materials Prices,

which is compiled by the U.S. Department

of Commerce, U.S. Department of Labor,

and Commodity Research Bureau, Inc.

3Robert S. Pindyck and Julio J. Rotemberg,

“The excess co-movement of commodity

prices,” National Bureau of Economic

Research, Washington, DC, working paper,

No. 2671, July 1988.

4Our forecasts were out of sample and were

recursively estimated using Kalman filter-

ing techniques from January 1970 to June

1994. The full sample period was January

1963 to June 1994.

David R. Allardice, Vice President and Director

of Regional Econ omic Programs and Statistics;

Janice Weiss, Editor.

ChicagoFed Letter is published monthly by the

Research Department of the Federal Reserve

Bank of Chicago. The views expressed are

the authors’ and are not necessarily those of

the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the

Federal Reserve System. Articles may be

reprinted if the source is credited and the

Research Department is provided with copies

of the reprints.

Chicago Fed Letterxs available without charge

from the Public Information Center, Federal

Reserve Bank of Chicago, P.O. Box 834,

Chicago, Illinois, 60690, (312) 322-5111.

ISSN 0895-0164

More intriguing information

1. NVESTIGATING LEXICAL ACQUISITION PATTERNS: CONTEXT AND COGNITION2. Wirkung einer Feiertagsbereinigung des Länderfinanzausgleichs: eine empirische Analyse des deutschen Finanzausgleichs

3. The Mathematical Components of Engineering

4. Labour Market Institutions and the Personal Distribution of Income in the OECD

5. Evolving robust and specialized car racing skills

6. The name is absent

7. Does Presenting Patients’ BMI Increase Documentation of Obesity?

8. THE WELFARE EFFECTS OF CONSUMING A CANCER PREVENTION DIET

9. The Dictator and the Parties A Study on Policy Co-operation in Mineral Economies

10. Economic Evaluation of Positron Emission Tomography (PET) in Non Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), CHERE Working Paper 2007/6