88

Karl Ove Moene and Michael Wallerstein

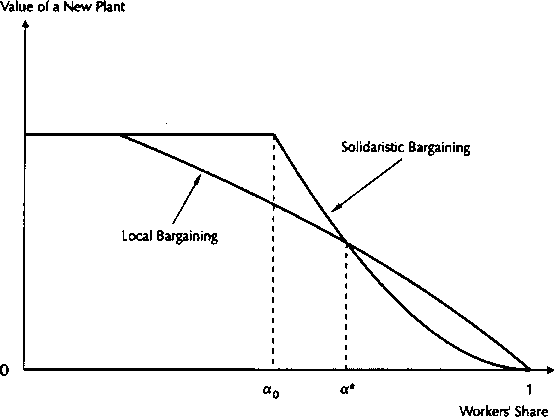

Figure 3

(and thus lowers investment) while solidaris-

tic bargaining has no effect. Thus, if α is

such that the wage with Solidaristic bargai-

ning is not much above workers' outside

option, Solidaristic bargaining raises the mar-

ket value of new plants relative to local bar-

gaining. Since the number of new plants

built is an increasing function of the market

value of new plants, entry is greater with soli-

daristic bargaining when CC is sufficiently low

(cc<α* in Figure 3).

As a increases, the productivity dif-

ference between the most efficient plant and

the industry average declines. At high level of

OC, wages are close to average productivity

and profits are low per period of operation in

either bargaining system. The period of time

over which plants are kept in operation,

however, is much shorter with Solidaristic

bargaining than with local bargaining when

alpha is high. Thus, the value of new plants

is higher with local bargaining than with

Solidaristic bargaining if alpha is sufficiently

large.7

Employment and Output

Total industry employment displays the

same pattern as the number of new plants. If

OC is not too large, employment is higher

with Solidaristic bargaining for the same rea-

sons that entry is higher. When α is low

enough to have a small effect with industry-

wide bargaining but sufficiently high to

increase the wage in the most productive

plants, employment and output is lower with

decentralized bargaining than with solidaris-

tic bargaining. The greater entry of new

plants under Solidaristic bargaining more

than compensates for the earlier closing of

older plants. When α is close to one, howe-

ver, both the age at which plants are closed

and the number of new plants that are built

is greater with local bargaining. Therefore,

employment and output are relatively higher

with decentralized bargaining when Ct is suf-

ficiently high.

Employers ' Wealth

Whatever the bargaining system, firms invest

until the value of new plants equals the cost

More intriguing information

1. Evolutionary Clustering in Indonesian Ethnic Textile Motifs2. Conservation Payments, Liquidity Constraints and Off-Farm Labor: Impact of the Grain for Green Program on Rural Households in China

3. Trade Liberalization, Firm Performance and Labour Market Outcomes in the Developing World: What Can We Learn from Micro-LevelData?

4. Temporary Work in Turbulent Times: The Swedish Experience

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. Bridging Micro- and Macro-Analyses of the EU Sugar Program: Methods and Insights

8. The name is absent

9. CREDIT SCORING, LOAN PRICING, AND FARM BUSINESS PERFORMANCE

10. CROSS-COMMODITY PERSPECTIVE ON CONTRACTING: EVIDENCE FROM MISSISSIPPI