Solidaristic Wage Bargaining

85

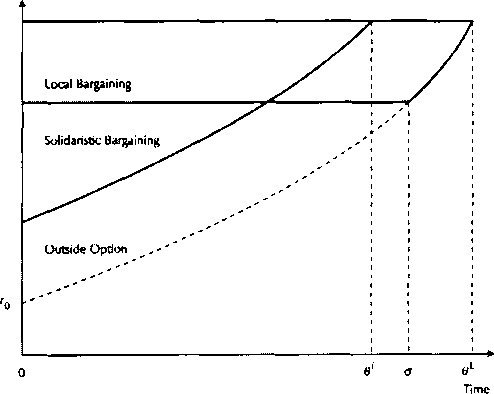

figure 2

Time Path of Wages with Local Bargaining

than σ but younger than θc pay workers

their outside option. The time path of wages

in a single plant with local bargaining is illu-

strated in Figure 2. The upper horizontal line

represents the revenues earned by a plant of a

given vintage. If workers' outside option rises

with the average level of productivity in the

economy, the outside option will be a expo-

nentially rising curve as drawn. As long as

the wage exceeds workers' outside option,

the wage in each plant is constant over time

since the negotiated wage depends on the

price, which is constant by assumption, and

productivity, which is determined by the

date the plant was built. As the plant grows

older and the outside option rises, the gap

between the union wage and workers' outsi-

de option falls. Eventually, at ɑ in Figure 2,

the outside option becomes binding and the

wage increases with r.

Since the wage with local bargaining

equals the outside option after the period ɑ,

the exit decision is to scrap the plant when

the value added per worker equals the outsi-

de option wage. Accordingly, the lifespan of

plants with local bargaining is independent

of the unions' share of the plant's revenue.

All plants pay a wage equal to workers' outsi-

de option once they get sufficiently old,

regardless of the bargaining power of the

local union. Although decentralized bargai-

ning does not affect firms' exit decision,

entry is discouraged. A higher union share

reduces the market value of new plants, since

the profits earned when the wage is higher

than the outside option are lower. A lower

value of new plants leads to fewer entrants.

As the number of plants that are constructed

each period declines, so does the industry's

output and employment.

With sunk costs of investment, the

union is able to appropriate some of the qua-

si-rents (the difference between the plant's

revenue and workers' outside option) earned

by the firm. Anticipation of the union's futu-

re bargaining strength causes firms to reduce

investment, which lowers aggregate employ-

ment. $ But once a plant is built, both the

employer and the local union have a com-

mon interest in maximizing the quasi-rents

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The name is absent

3. The Challenge of Urban Regeneration in Deprived European Neighbourhoods - a Partnership Approach

4. Gender stereotyping and wage discrimination among Italian graduates

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. The name is absent

8. Rent Dissipation in Chartered Recreational Fishing: Inside the Black Box

9. The Social Context as a Determinant of Teacher Motivational Strategies in Physical Education

10. The Economic Value of Basin Protection to Improve the Quality and Reliability of Potable Water Supply: Some Evidence from Ecuador