1960s, the U.S. market was characterized by

surplus stocks and fairly stable prices. The only

significant source of instability was the weather.

However, as U.S. agriculture has moved more

prominently into world markets, the situation has

changed.

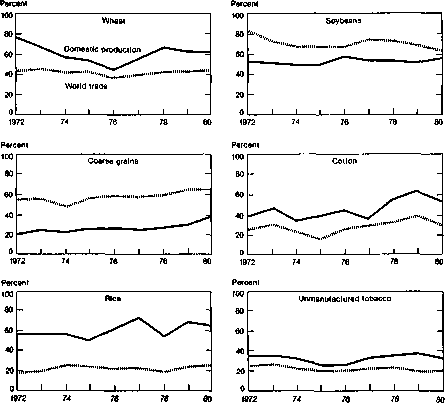

The importance of exports to U.S. agriculture

is demonstrated in Figure 1, with the share of

domestic production going to world markets that

are highly significant for wheat, soybeans, rice

and cotton. Of perhaps even greater importance

is the proportion that U.S. exports make up of

total world trade in various farm products (Fig-

ure 1). Coarse grains and soybeans originating on

U.S. farms have consistently accounted for more

than half of the world trade in these com-

modities; wheat trade is also highly dependent on

U.S. participation. Taken together, these two

measures demonstrate the problematic nature of

agricultural exports—their critical importance to

domestic producers and the exposure to world

market shocks that they permit. In part, this ex-

posure is a function of the dominant position of

U.S. commodities in particular markets. The fact

that the United States holds an estimated one-

quarter of the world’s wheat stocks and nearly

half of the world’s coarse grain stocks is also

important. Because of the exposure that exports

permit, changes in importing countries’ produc-

tion, general economy, and government policies

are transferred to U.S. farmers through the ex-

port market. For instance, the several countries

that employ policies protecting their domestic

consumers and producers from the price and

quantity adjustments of the world market effec-

FIGURE 1. U.S. Exports: Share of Domestic

Production and World Trade

Crop ум» for Siiam ol domestic production. Milled rice.

Source: 1981 Handbook for Agricultural Charts, Agricul-

ture Handbook No. 592, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

tively shift and exacerbate the adjustment shock

onto residual suppliers such as the United States.

As indicated in Table 2, the level of interannual

variability in the foreign demand for major export

commodities has trended upward throughout the

past 30 years. Consider the most recent 15-year

period in comparison to the 1950-64 period: in-

terannual variability for wheat exports was

nearly double; for coarse grains, it was more than

quadruple; for rice, it was nearly 50 percent

greater; and for soybeans it was more than 7

times higher. As a percent of exports, these an-

nual swings in foreign demand now amount to

almost 15 percent for wheat and 10 percent for

coarse grains.

Although not so clearly documented, there ap-

pears to be a rather strong cause and effect rela-

tionship between this variation in exports and

that which has been experienced in farm prices

and incomes. Examination of the coefficients of

variation for the index of prices received (Table

3) shows a marked increase in variability moving

from the 1950s, through the 1960s, and up to the

late 1970s. This is especially true for crop prices.

Cash receipts follow a similar pattern (Table 3)

with variation noticeably greater during the

1970s. These results tend to track quite closely

with the increase in variability noted for export

volume.

Farm income also exhibits a significant in-

crease in variability by the mid 1970s (Table 3).

TABLE 2. Interannual Variability in Foreign

Demand for U.S. Productsa

|

Years |

Wheat |

Coarse |

Rice |

Soybeans |

Soybean |

Total |

|

1950-64 |

2,920 |

1,880 |

— 1,000 170 |

metric tons___ 260 |

290 |

5,520 |

|

1951-65 |

2,800 |

2,125 |

170 |

300 |

380 |

5,805 |

|

1952-66 |

2,275 |

1,950 |

190 |

300 |

390 |

5,105 |

|

1953-67 |

2,450 |

1,950 |

175 |

290 |

390 |

5,255 |

|

1954-68 |

. 3,325 |

2,800 |

142 |

270 |

370 |

6,907 |

|

1955-69 |

3,475 |

3,000 |

140 |

885 |

380 |

6,880 |

|

1956-70 |

3,300 |

3,250 |

190 |

990 |

' 38'5 ' ’ |

• 8-,115- |

|

1957-71 |

3,450 |

3,125 |

185 |

950 |

340 |

8,050 |

|

1958-72 |

4,085 |

4,725 |

195 |

960 |

310 |

10,275 |

|

1959-73 |

4,730 |

5,555 |

215 |

1,010 |

305 |

11,815 |

|

1960-74 |

4,725 |

5,590 |

205 |

1,165 |

405 |

12,090 |

|

1961-75 |

4,900 |

6,605 |

215 |

1,160 |

420 |

13,300 |

|

1962-76 |

4,875 |

6,830 |

200 |

1,200 |

490 |

13,595 |

|

1963-77 |

4,925 |

7,075 |

195 |

1,310 |

475 |

13,980 |

|

1964-78 |

5,125 |

7,290 |

220 |

1,495 |

490 |

Ii,620 |

|

1965-79 |

5,350 |

7,425 |

230 |

1,715 |

540 |

15,260 |

|

1966-80 |

5,475 |

7,650 |

245 |

1,925 |

595 |

15,890 |

a Estimates of variability based on standard errors of the

regression for successive best fit 15 linear and curvilinear

time trends.

Source: O’Brien, P. M. “Global Prospects for Agricul-

ture,” Agricultural-Food Policy Review: Perspectives for the

1980’s, AFPR-4, ESS, USDA, 1981, p. 15.

30

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The problem of anglophone squint

3. Partner Selection Criteria in Strategic Alliances When to Ally with Weak Partners

4. HOW WILL PRODUCTION, MARKETING, AND CONSUMPTION BE COORDINATED? FROM A FARM ORGANIZATION VIEWPOINT

5. News Not Noise: Socially Aware Information Filtering

6. Expectation Formation and Endogenous Fluctuations in Aggregate Demand

7. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews

8. Optimal Tax Policy when Firms are Internationally Mobile

9. Optimal Private and Public Harvesting under Spatial and Temporal Interdependence

10. Bridging Micro- and Macro-Analyses of the EU Sugar Program: Methods and Insights