|

4t |

£2,616 |

£3,168 |

£2,078 |

£2,457 |

|

5tth |

£3,210 |

£3,010 |

£2,469 |

£2,379 |

|

6th |

£3,419 |

£2,852 |

£2,575 |

£2,306 |

|

7th |

£3,356 |

£2,710 |

£2,557 |

£2,248 |

|

8t |

£3,156 |

£2,552 |

£2,463 |

£2,154 |

|

9th |

£2,999 |

£2,459 |

£2,411 |

£2,068 |

|

Richest |

£2,670 |

£2,234 |

£2,242 |

£1,931 |

|

ALL |

£2,464 |

£2,879 |

1936 |

£2,278________ |

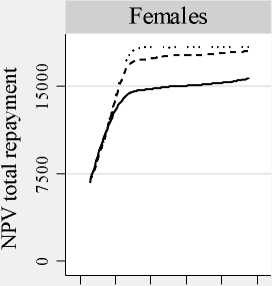

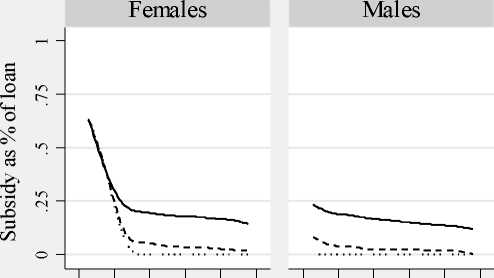

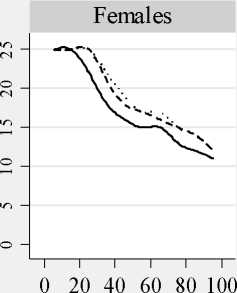

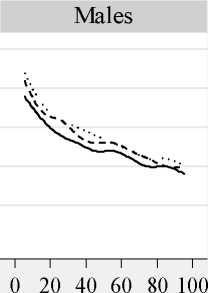

Figure . Comparing possible future reforms: removing interest subsidies

NPV total repayment

0 20 40 60 80 100

Subsidy as % of loan

0 20 40 60 80 100 0 20 40 60 80 100 0 20 40 60 80 100

Years to repay loan

New system

NZ system

2.5% real int

Percentile of the lifetime earnings distribution

Other options for reducing the taxpayer cost of graduate loans would include

extending the length of time after which the loans are written off beyond 25 years, or

reducing the repayment threshold, for example by removing the default indexation

provision after 2010, so that its real value erodes over time.23 It should be noted that

23 The current system of up-rating the £15,000 threshold in line with inflation means that year on year

the system becomes less progressive for relatively low earners. This is because the threshold increases

at a relatively slower rate than earnings. So, each year fewer and fewer individuals have earnings below

the threshold, and therefore the subsidies to these individuals are lower. Indeed, considering the effects

of the reforms for graduates in 2009 rather than 2011, as in previous versions of this paper, we see that

the system is less progressive for the 2011 cohort of graduates for this reason. This is unlike the

situation in Australia for example, weher the threshold is set relative to average earnings to ensure

25

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The name is absent

3. CAPACITAÇÃO GERENCIAL DE AGRICULTORES FAMILIARES: UMA PROPOSTA METODOLÓGICA DE EXTENSÃO RURAL

4. The name is absent

5. The name is absent

6. Banking Supervision in Integrated Financial Markets: Implications for the EU

7. The name is absent

8. QUEST II. A Multi-Country Business Cycle and Growth Model

9. The name is absent

10. Implementation of Rule Based Algorithm for Sandhi-Vicheda Of Compound Hindi Words