16

organizational change. Government policies in this country currently do not represent a

major impediment to or constraint on business investment, innovation and human capital

formation, and hence on productivity growth. It is extremely unlikely that Canada’s

potential labour productivity growth is double its current trend productivity growth

(estimated to be around 1.5 per cent per year by the Bank of Canada (2006)). In other

words, in a world where Canadian governments institute the policies most conducive to

productivity growth, it is very unlikely that long-run productivity growth could double.

This does not mean that there is no potential for productivity improvement

through better public policies. Indeed, this is the premise of the paper. But one must be

realistic about the potential for improvement. In my view, a reasonable ballpark upper

bound estimate of the impact of better public policy on labour productivity growth in the

medium term might be 0.5 percentage points increase per year. Of course, trend labour

productivity growth could potentially pick up by much more than 0.5 points due to non-

public policy related factors such as more rapid technological progress and faster capital

accumulation. Indeed, few if any economists argue that the large acceleration of labour

productivity growth in the United States since 1995 has been primarily driven by

improved public policy.

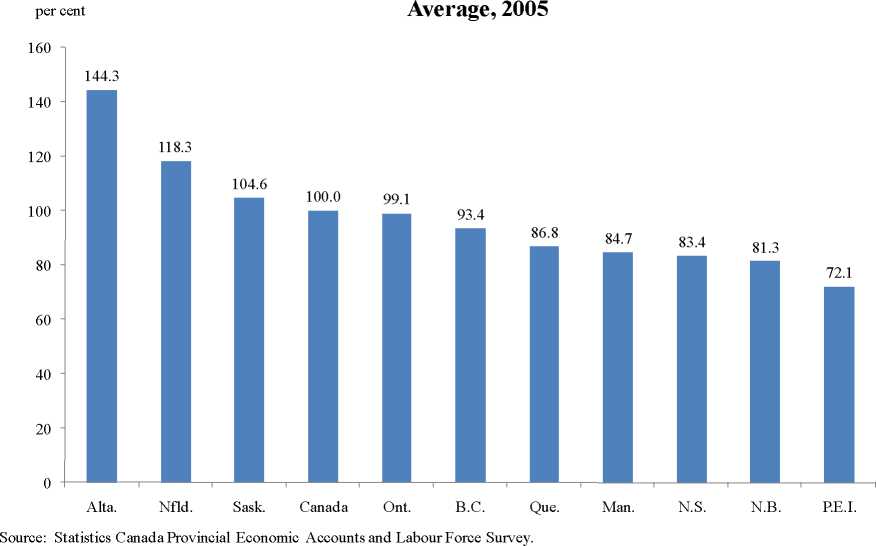

Chart 3: Provincial GDP per Worker as a Proportion of the National

This impact of better public policy on productivity may seem small, but given the

size of the economy, in absolute terms it is huge. In 2006, the nominal value of GDP in

Canada was around $1.4 trillion or $1,400 billion. An increase in productivity and hence

nominal GDP of 0.5 per cent would amount to $7 billion per year. This is massive. Public

More intriguing information

1. Government spending composition, technical change and wage inequality2. The name is absent

3. Nach der Einführung von Arbeitslosengeld II: deutlich mehr Verlierer als Gewinner unter den Hilfeempfängern

4. The InnoRegio-program: a new way to promote regional innovation networks - empirical results of the complementary research -

5. Developments and Development Directions of Electronic Trade Platforms in US and European Agri-Food Markets: Impact on Sector Organization

6. Transgression et Contestation Dans Ie conte diderotien. Pierre Hartmann Strasbourg

7. Ahorro y crecimiento: alguna evidencia para la economía argentina, 1970-2004

8. Micro-strategies of Contextualization Cross-national Transfer of Socially Responsible Investment

9. Imperfect competition and congestion in the City

10. The Trade Effects of MERCOSUR and The Andean Community on U.S. Cotton Exports to CBI countries