Changes in the mix of students

and non-students

The youth population comprises students and

non-students with very different participation

rates. Although many full-time students work or

search for work during the school year, they are

less likely than non-students to be participating in

the labour force. Even at the peak of economic ac-

tivity in the 1980s, the participation rate for stu-

dents in Canada was only half that of non-stu-

dents.9 Thus, a rise in attendance rates will

produce a lower overall youth participation rate,

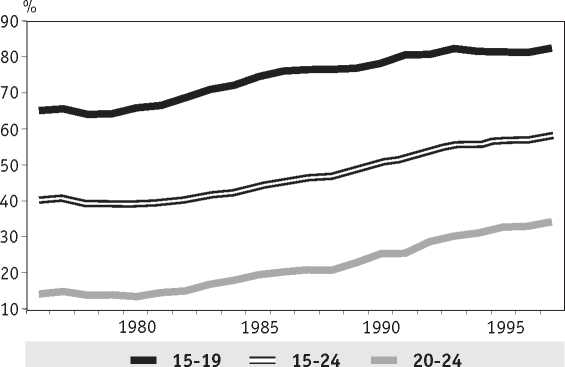

other things being equal.10 In Canada the full-

time school attendance rate rose to more than 58

per cent in 1997 from 50 per cent in 1989 (Chart

6), which, according to one estimate, accounted

for about 50 per cent of the decline in the youth

participation rate from 1989 to 1997.11

The rise from 1989 to 1997 in the full-time

school attendance rate in Canada for teens was

only about half the increase experienced by

young adults. It therefore had a much smaller ef-

fect on the teens’ than on the young adults’ par-

ticipation rate, accounting for only about 20 per

cent of the decline in the participation rate of

teens compared with 90 per cent of the decline in

the rate of young adults (Jennings, 1998).

For both the 16-19 and the 20-24 age groups the

rise in attendance rates was larger in Canada than

in the United States in 1989-97 according to a

measure that includes part-time students.12 From

being roughly equal in 1989, the teen rate rose

seven percentage points for Canada compared

with 4.9 percentage points for the United States.

The attendance rate for those aged 20-24 was one

percentage point higher in Canada than in the

United States in 1989 and rose 10.9 percentage

points compared with 7.2 percentage points in the

United States. If most of the rise in the United

States were structural, then using it as a bench-

mark, the extra growth in Canada may be inter-

preted as a cyclical response. These assumptions,

however, imply that the rise in youth school atten-

dance rates do not account for any of the differ-

ence between the falls in the participation rates of

the two countries.

Faster growth in the attendance rates as the em-

ployment rate fell between 1989 and 1992 indi-

cates that, particularly for teens, they do respond

to cyclical developments. The incentive to stay in

school is likely stronger when there are fewer low-

Chart 6 Full-time students as a proportion of population

of same age in Canada

skill job opportunities, and these opportunities

tend to be sensitive to the business cycle. The

1990-91 recession had a disproportionate effect

on teenagers encouraging many to stay in school.

Data on school attendance in the United States are

available from the late 1940s, whereas in Canada,

they go back only to 1976. From an examination

of the U.S. data cyclical effects appear to be small

relative to longer-term trends.

The recent growth in U.S. male attendance

rates was a continuation of an upward movement

dating back to the beginning of the 1980s, after a

fall related to the Vietnam War had petered out.

By the mid-1990s, rates were in the region of the

previous peaks and appear to be still holding. Fe-

male rates, on the other hand, have been rising

very steadily in the United States for 50 years and

have now virtually converged with their male

counterparts. Strong gains were posted by all but

16- and 17 year olds. These developments suggest

that the rise in the school attendance rate is

largely structural. The Canadian experience has

been similar to that of the United States since the

early 1980s. Women’s rates grew more strongly

than men’s. Teen rates have begun to flatten out in

recent years but young adults’ rates have contin-

ued to rise. It therefore seems reasonable to as-

sume that some of the longer-term characteristics

of the U.S. experience, especially for women, are

present also in Canada and that a large share of

the increase in the attendance rate in the 1990s

was likely structural.

Further evidence of the structural nature of the

increase in school attendance rates is the fact that

Summer 1999

Canadian Business Economics

More intriguing information

1. Does South Africa Have the Potential and Capacity to Grow at 7 Per Cent?: A Labour Market Perspective2. The name is absent

3. EFFICIENCY LOSS AND TRADABLE PERMITS

4. Banking Supervision in Integrated Financial Markets: Implications for the EU

5. NATURAL RESOURCE SUPPLY CONSTRAINTS AND REGIONAL ECONOMIC ANALYSIS: A COMPUTABLE GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM APPROACH

6. A dynamic approach to the tendency of industries to cluster

7. Equity Markets and Economic Development: What Do We Know

8. Applications of Evolutionary Economic Geography

9. THE CHANGING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FEDERAL, STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS

10. The value-added of primary schools: what is it really measuring?