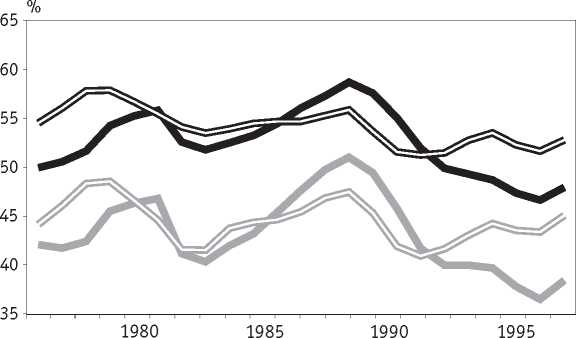

Chart 8 Participation and employment rates, both sexes,

in Canada and the United States

Canadian participation rate Canadian employment rate

= U.S. participation rate = U.S. employment rate

Note: Canadian data for 15-19 year olds; U.S. data for 16-19 year olds.

Further disaggregation of this group strength-

ens the case that, while this process is not yet

over, additional ratcheting upward will be much

smaller. In the United States, participation rates

for women with children under 18 have been ris-

ing faster than those of other women, with the re-

sult there has been a considerable shrinking of the

difference between the rates of these two

groups.20 The other source of growth in the rate

for U.S. core-age women since the mid-1980s has

been in the group aged 45-54 without children.

The degree of convergence of the rates for these

sub-groups, as well as the rates for men and

women, has already been considerable. In addi-

tion, the proportion of the year that women have

been spending in the workforce on average has

now reached 11 months compared with 11.5

months for men.21 These developments indicate

there is less room for growth in the participation

rate for women aged 25-54. Similar movements

appear to have been taking place in Canada. In

fact, the rate for women aged 25-44 is now higher

in Canada than in the United States. However, the

rate for the 45-54 age group in Canada, which rose

significantly in the 1990s, is still below that for

U.S. women of the same age and below that for

Canadian women aged 25-44. There may, thus, be

more room for the participation rate of Canadian

women to rise than for women in the United

States, despite the fact that the rates for Canadian

and U.S. core-age women were virtually identical

in 1997.

One explanation for the tendency for women’s

participation rates to increase while men’s stag-

nate or decline may be that women are more flex-

ible over the kind of jobs they will fill. For exam-

ple, there is some evidence women’s greater

willingness to take low-paying jobs, for which

they are overqualified, while they are juggling

work and domestic duties.22 The relatively

greater rise in full-time school attendance rate for

young women than for young men, may also be

responsible for a stronger influence on the partici-

pation rate for women in the core group.

In Canada, changes to EI may eventually

weaken labour force attachment with the result

that a cyclical increase in the overall employment

rate for those in the core group may not be accom-

panied by as much of a rise in the participation

rate. By 2006 the participation rate of the core-age

group appears to have room to move to about

three percentage points above the 1996 level but

only if male rates rise slightly (say by one percent-

age point). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics as-

sumes the male rate in the United States will de-

cline over the next decade, and projects a 1.7

percentage point increase in the total core-age rate

from 1996 to 2006 (Fullerton, 1997: Table 4).

Youth: Ages 24 and under

Participation rates are more cyclical for youths

than for adults but, if a large part of the increase in

school attendance rate is structural, the participa-

tion rates may not return to the peak level of the

late 1980s any time soon. For the United States,

that development would be a continuation of a

pattern that was evident in the 1980s for teens and

men aged 20-24.

Teens: 19 years and under

The labour market experiences of teens (15-19

in Canada, 16-19 in the United States) and young

adults (20-24) are sufficiently different to warrant

separate treatment here.23

In both Canada and the United States, the at-

tachment of teenagers to the labour force is rela-

tively weak, driven largely by job opportunities.

Their participation rates are, therefore, very cycli-

cal, tracking their employment rate very closely

for some time (Charts 8 and 9). This is not surpris-

ing since, during the school year, most teens are in

school full-time and thus available for few hours

of work each week.25

Canadian Business Economics

Summer 1999

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The name is absent

3. 03-01 "Read My Lips: More New Tax Cuts - The Distributional Impacts of Repealing Dividend Taxation"

4. Learning-by-Exporting? Firm-Level Evidence for UK Manufacturing and Services Sectors

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. Natural Resources: Curse or Blessing?

8. TINKERING WITH VALUATION ESTIMATES: IS THERE A FUTURE FOR WILLINGNESS TO ACCEPT MEASURES?

9. Family, social security and social insurance: General remarks and the present discussion in Germany as a case study

10. Effects of red light and loud noise on the rate at which monkeys sample the sensory environment