Although the participation rate for the teen-

aged group was lower in Canada than in the

United States in the 1970s, it had caught up by the

beginning of the 1980s and overtaken the U.S. rate

by the end of the decade. The relatively stronger

expansion in Canada was a significant factor in

the latter occurrence. The drop in participation

rates in the 1990-91 recession, though significant

in both countries, was much more severe in Can-

ada and, while the rates began to recover some-

what in the United States after 1992, they contin-

ued to fall in Canada. Nevertheless, the U.S. rates

have not returned to their pre-recession levels,

suggesting structural factors may be playing a

role.

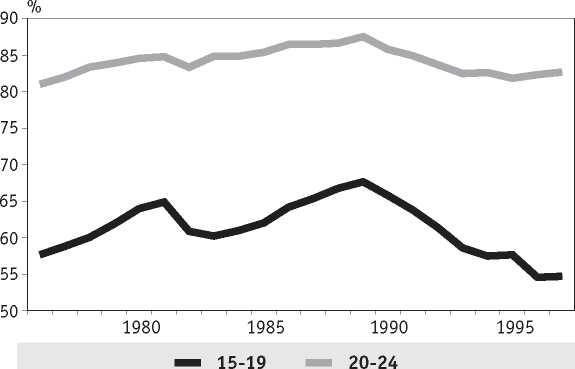

Chart 9 Summer participation rates, Canada

Note: Data not seasonally adjusted.

As the increase in full-time school attendance

in Canada can account for only a small part of the

decline in the participation rate, most of the de-

cline stemmed from falling participation rates for

students and non-students. The participation rate

for teenage students in Canada fell about 12 per-

centage points between 1989 and 1997, reflecting

a particularly difficult job market for these young

people, one that was much more severe for both

students and non-students than for older youths

(Statistics Canada, 1997). The performance of

teen participation rates in the summer months en-

forces this view (Chart 9). In addition to the weak-

ness of the economy, Canadian students may also

have been affected by the restructuring in sectors

that traditionally provided the kind of part-time or

summer jobs filled by teenagers, such as retail,

which accounts for about 25 per cent of student

employment.

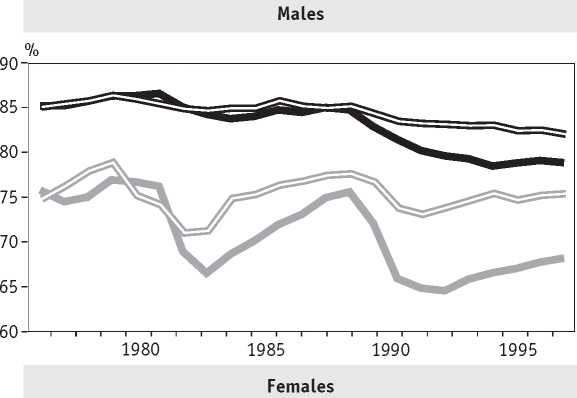

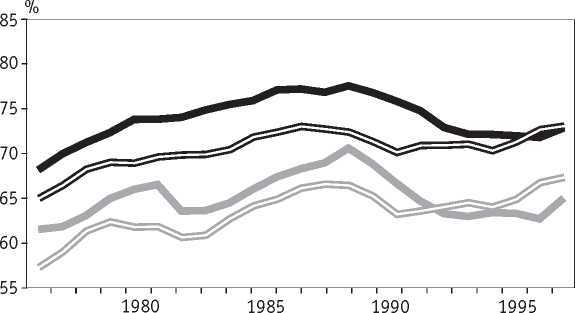

Chart 10 Participation and employment rates, 20-24 age

group

Canadian teenagers who are not in school have

also had difficulty finding jobs in the 1990s.25

Their participation rate fell by almost seven per-

centage points during the recession, and by 1997

it had recovered by only two percentage points.

Apart from the cyclical effect, the shrinking per-

centage of jobs that now require more than a basic

level of literacy may have negatively affected the

search intensity of both United States and Cana-

dian teens.26 The increases in payroll taxes, in-

cluding the extension of EI premiums to all hours

worked, may also have discouraged job search

among Canadian teens. The rise in the minimum

wage in Canada relative to the average wage in

the 1990s, in contrast to its decline from the mid-

1970s until the mid-1980s, may have had a nega-

tive effect on the demand side of the labour mar-

ket, which in turn dampened the supply side. The

Canadian participation rate Canadian employment rate

= U.S. participation rate = U.S. employment rate

Summer 1999

Canadian Business Economics

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The Response of Ethiopian Grain Markets to Liberalization

3. The open method of co-ordination: Some remarks regarding old-age security within an enlarged European Union

4. THE EFFECT OF MARKETING COOPERATIVES ON COST-REDUCING PROCESS INNOVATION ACTIVITY

5. Innovation and business performance - a provisional multi-regional analysis

6. Text of a letter

7. Flatliners: Ideology and Rational Learning in the Diffusion of the Flat Tax

8. Discourse Patterns in First Language Use at Hcme and Second Language Learning at School: an Ethnographic Approach

9. Response speeds of direct and securitized real estate to shocks in the fundamentals

10. Federal Tax-Transfer Policy and Intergovernmental Pre-Commitment