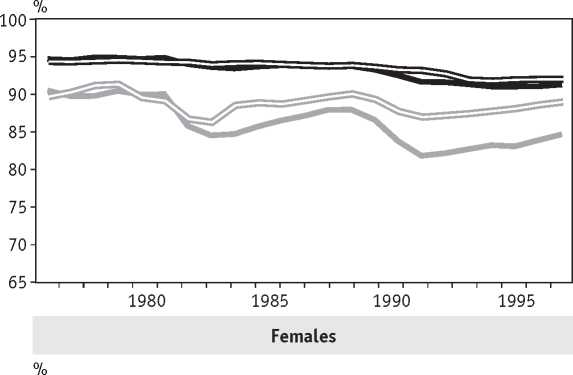

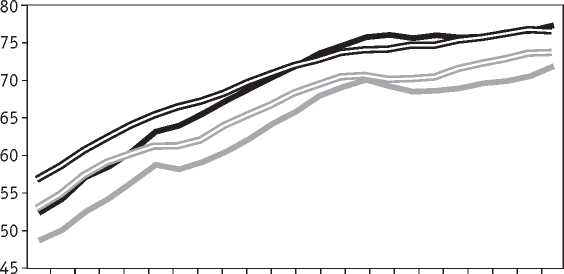

Chart 7 Participation and employment rates 25-54

Males

1980 1985 1990 1995

Canadian participation rate Canadian employment rate

U.S. participation rate U.S. employment rate

they rose in the 1980s in both countries, even as

employment rates increased, perhaps responding

to factors such as the continuing shift in demand

from low- to higher-skilled jobs.

The premium paid to workers with higher lev-

els of education is one incentive to spend more

years in school. Since, in Canada, there is little

evidence these premiums have increased since

the 1970s, they do not account for the rising trend

in attendance rates (Bar-Or et. al., 1995, Beaudry

and Green, 1997). The failure for these premiums

to rise may be because the supply of educated

youth has been growing faster than the demand

for such workers. Nevertheless, the lower unem-

ployment rate for those with higher levels of edu-

cation13 may be a sufficiently strong incentive for

relatively more young people to choose to stay in

school and thus improve their employment pros-

pects.14

Interpreting the differences between Canadian

and U.S. school attendance rate increases from

1989 to 1997 as the cyclical component of the Ca-

nadian increase implies that for teens the struc-

tural increase in the attendance rate accounted for

about 1.75 percentage points, or 15 per cent, of

the 12 percentage point fall in their participation

rate. For young adults the structural component

would account for 3.4 percentage points, or 60 per

cent, of the drop of 5.7 percentage points in their

participation rate. These two effects combined ap-

pear to account for about 0.4 percentage points of

the decline in the aggregate participation rate.15

Possible Structural

Influences on

Participation Rates of

Major Age/Gender

Groups

The disaggregrated data for the three age

groups considered here show that the similarity

before 1990 between the aggregate Canadian and

U.S. participation rate levels and trends extended

to most sub-groups. Even beyond 1990 there were

remarkable similarities in some groups though

the aggregate rates were so different.

The core labour force: ages 25-54

For the core labour force group as a whole

(aged 25-54), the steeply rising trend in the female

participation rates in the 1970s and 1980s out-

weighed the declining trend in the rates for men.

In the 1990s, however, the rate for women flat-

tened out in Canada and slowed considerably in

the United States, while the decline in the rate for

men picked up (Chart 7). Because this group has

a strong attachment to the labour force, its partici-

pation rate is relatively insensitive to changes in

the business cycle.

Since the 1981-82 recession, Canadians have

stayed in the labour force almost to the same de-

gree that Americans have — both men and

women — while employment rates have gener-

ally been much lower in Canada. This indicates

that Canadian adults have a stronger attachment

to the labour force. The similarity in participation

rates in the 1990s is particularly remarkable, tak-

Canadian Business Economics

Summer 1999

More intriguing information

1. Critical Race Theory and Education: Racism and antiracism in educational theory and praxis David Gillborn*2. The name is absent

3. The Challenge of Urban Regeneration in Deprived European Neighbourhoods - a Partnership Approach

4. INTERACTION EFFECTS OF PROMOTION, RESEARCH, AND PRICE SUPPORT PROGRAMS FOR U.S. COTTON

5. The name is absent

6. On the estimation of hospital cost: the approach

7. Tariff Escalation and Invasive Species Risk

8. The name is absent

9. Income Taxation when Markets are Incomplete

10. The name is absent