tachment to the labour force than non-students,

in the population and, in Canada, the changes in

EI eligibility may also be loosening the attach-

ment of this age group to the labour force. The re-

lationship between the Canadian participation

and employment rates may, therefore, become

even closer in the future.

Primarily because of the higher school atten-

dance rate in 1997 than in 1989, a large part of

which appears to be permanent, an increase of no

more than three to four percentage points from

1996 to 2006 appears likely. The maintenance of

all the gains in the attendance rate would, by it-

self, preclude a return of the participation rate to

the peak level reached in 1989. Although the par-

ticipation rates for Canadian students and non-

students can be expected to continue to make cy-

clical gains, the gap between the participation and

the employment rates may shrink toward that of

the United States, in response to changed EI rules.

In contrast with this projection, the BLS is project-

ing a decline of 2.6 percentage points for this

group by 2006 in the United States (Fullerton,

1997: Table 4).

Older workers: Ages 55 and over

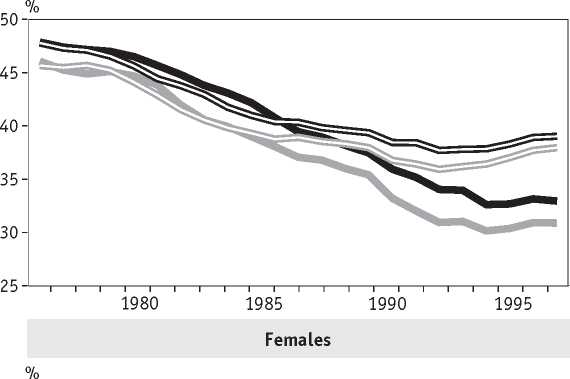

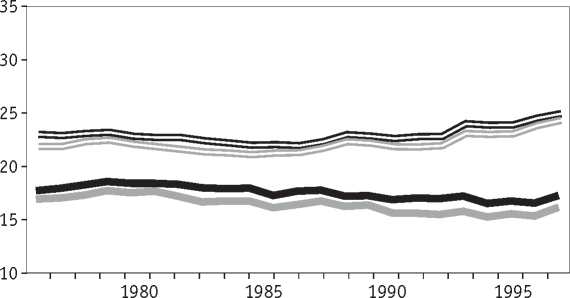

The most striking characteristics of participa-

tion rates for workers aged 55 and over in both

countries are the dramatic decline in the male rate

from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s and the

close relationship between participation and em-

ployment rates, indicating a weak attachment to

the labour force (Chart 11).29 Both the employ-

ment and participation rates for men in the two

countries ended their decline in the 1990s, and

have even risen slightly in the United States. Par-

ticipation rates for women, which are much lower

in Canada than in the United States, exhibited a

very weak downward trend until 1986. Since

then, these rates have diverged even more as the

U.S. rate ratcheted upward. The long-term nature

of the downward trend in this older group’s par-

ticipation rates suggests structural factors have

been more important than cyclical forces in their

labour market decisions. It is even difficult to find

a purely cyclical reason for the recent change in

the trend in the male rates.

There is a great deal of variation in participa-

tion rate patterns among the various age groups

that make up the aggregate 55 and over group. For

example, the rate for youngest sub-group of

women (aged 55-59) rose decisively in the 1980s.

Chart 11 Participation and employment rates,

55 and over

Males

Canadian participation rate Canadian employment rate

U.S. participation rate U.S. employment rate

Since the same group has been exhibiting compa-

rable behaviour in the United States, it appears

the ratcheting-up phenomenon of women’s par-

ticipation rates may be affecting this age group

and, may affect the 60-64 age group eventually.

In the United States, a new development ap-

pears to be taking place that may be a harbinger

for Canada. The change in direction in the partici-

pation rate for U.S. men aged 55 and over was

caused by an increase of more than two percent-

age points from 1986 to 1996 in the rate for the

65-75 age group.30 Since the rise continued

throughout the recession, when for most other

U.S. male groups it declined, it appears to be

structural. In Canada, the participation rate for

males aged 65-69 stopped falling in the 1990s,

suggesting it may follow the new trend for older

American men.

Summer 1999

Canadian Business Economics

11

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The Impact of Financial Openness on Economic Integration: Evidence from the Europe and the Cis

3. The name is absent

4. Job quality and labour market performance

5. Micro-strategies of Contextualization Cross-national Transfer of Socially Responsible Investment

6. Can a Robot Hear Music? Can a Robot Dance? Can a Robot Tell What it Knows or Intends to Do? Can it Feel Pride or Shame in Company?

7. Dual Track Reforms: With and Without Losers

8. AN IMPROVED 2D OPTICAL FLOW SENSOR FOR MOTION SEGMENTATION

9. The name is absent

10. Manufacturing Earnings and Cycles: New Evidence