S

Technological Innovation

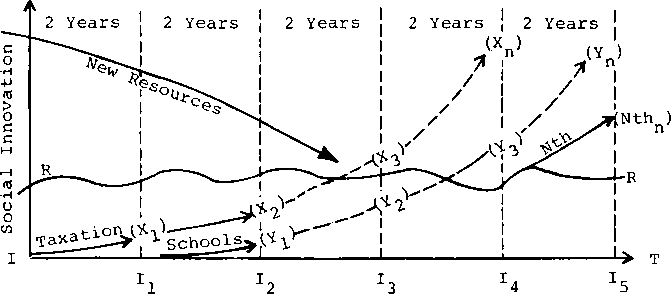

Figure 5. Flow of Resources to New Research and

Educational Functions, Reconceptualization Stage

Act II” (the social innovation research equivalent of the original

Hatch Act) and “Smith-Lever Act II” can build a permanent fiscal

base for these activities in the university as “definite and distinct” re-

search and educational capabilities. The equivalent Hatch Act II and

Smith-Lever Act II would tie in resources with federal agencies

different from their present finkage solely to the Department of

Agriculture.

If all of this has begun to have a familiar ring—it should. This

whole strategy is copied from the process used by the resident faculty,

near the turn of the century, to “move” the land-grant university from

on-campus teaching to teaching people in the countryside, to give them

knowledge for practical application. A “definite and distinct” research

and extension capability became a reality, with funds flowing into the

system from new state and federal legislative acts and grants-in-aid.

We need a major innovation within our system a la the historic

period 1887-1914, which can happen when its time has arrived. We

can profit from the lessons of our recent experience in the modest

though transient success of prototype operations. The experience of

our own illustrious past, and the record of present innovation-oriented

firms can enable us to achieve a research and educational capacity

which is in scale with the demands of people in our society. We can

foster diversity in the style and performance of our university research

and educational functions. To do so will require more than the mar-

ginal increments of faculty time. Some important faculty will need to

devote their time temporarily to articulating and dramatizing the new

23

More intriguing information

1. AN IMPROVED 2D OPTICAL FLOW SENSOR FOR MOTION SEGMENTATION2. Change in firm population and spatial variations: The case of Turkey

3. Types of Tax Concessions for Promoting Investment in Free Economic and Trade Areas

4. The Role of Land Retirement Programs for Management of Water Resources

5. LABOR POLICY AND THE OVER-ALL ECONOMY

6. Credit Markets and the Propagation of Monetary Policy Shocks

7. Examining the Regional Aspect of Foreign Direct Investment to Developing Countries

8. TRADE NEGOTIATIONS AND THE FUTURE OF AMERICAN AGRICULTURE

9. The name is absent

10. The name is absent