more rapidly than p because commuting costs are more important for labour than transport

costs for commodity prices. In addition, the labour force is inherently regional, whilst

commodities typically are produced in other regions or abroad, implying that the effect of

local transport system improvements are greater for w than for p.

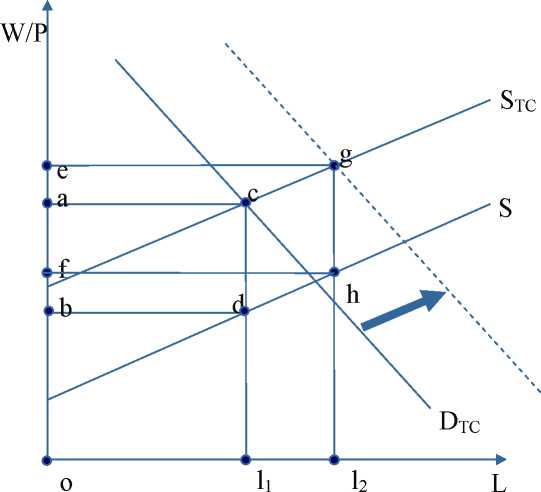

Figur 3 Technological externalities associated with transport system improvements

In the case of technological externalities, shown in figure 3, demand for labour at a given real

wage increases because of non-market interaction effects arising from transactions undertaken

by other agents. In this case of technological change, the demand curve for labour including

transport costs (DTC) shifts to the right, creating a new labour market equilibrium, as shown in

figure 3, moving from c to g. This means that demand for labour increases from l1 to l2 and

the real wage increases from a to e. The wage bill increases from acl1o to egl2o. The change in

total expenditure on transport is shown by cghd.

3. Proximity, income and externalities in Denmark

The previous section outlined a priori expectations concerning the relationship between

changes in the transport system and externality effects in relation to the labour market. First,

that there is a positive relationship between changes in transport costs and the level of real

wages in the case of changes in accessibility in the labour and commodity markets, this being

the effect of pecuniary externalities. Second, there is a negative relationship between changes

in transport costs and changes in the level of real wages in the case of changes in accessibility

to urban centres. This is the effect of urban (technological) externalities. The analysis also

revealed that it is important to distinguish between the direct effects of externalities (which

appear at the place of production and in the unit of production) and the end user effects, which

More intriguing information

1. The Variable-Rate Decision for Multiple Inputs with Multiple Management Zones2. Educational Inequalities Among School Leavers in Ireland 1979-1994

3. AN IMPROVED 2D OPTICAL FLOW SENSOR FOR MOTION SEGMENTATION

4. The name is absent

5. Ultrametric Distance in Syntax

6. The name is absent

7. A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON UNDERINVESTMENT IN AGRICULTURAL R&D

8. An Efficient Secure Multimodal Biometric Fusion Using Palmprint and Face Image

9. KNOWLEDGE EVOLUTION

10. Return Predictability and Stock Market Crashes in a Simple Rational Expectations Model