reactive behaviours, which depend strongly of an

external stimulus, or a set or sequence of external

stimuli (McFarland, 1981). Examples of these can be

locomotion patterns. These behaviours (and the ones

which follow) require an action selection process,

whereas reflex behaviours are executed whenever the

triggering stimulus is present. Motivated behaviours do

not only depend on external stimuli (or the absence of

a specific stimulus), but also on internal motivations.

For example, “exploration for food” can be performed

when there is the internal motivation “hunger”. The

previous types of behaviour have been modelled with

behaviour-based systems (BBS) (e.g. Brooks, 1986;

Beer, 1990; Maes, 1990; 1993; Hallam, Halperin and

Hallam, 1994; Gonzalez, 2000; Gershenson, 2001).

Reasoned behaviours are the ones which are

determined by manipulations of abstract concepts or

representations. Preparing yourself for a trip would be

an example. You would like to make plans, for which

you would need to have abstract representations, and

very probably a language (Clark, 1998), and to

manipulate these representations. This manipulation

can be considered as the use of a logic. This level has

been modelled with knowledge-based systems (KBS)

(e.g. Newell and Simon, 1972; Lenat and Feigenbaum,

1992). We could speculate about conscious behaviours,

without entering the debate of the definition

consciousness, just saying that they are behaviours that

are determined by the individual’s consciousness. We

do not believe that there is an “ultimate” level of

behaviour. We could, in theory, always find behaviours

produced by mechanisms more and more complex. But

for now we have enough trying to model behaviours

less complex than reasoned ones. If we cannot clearly

identify further levels, there is no sense in trying to

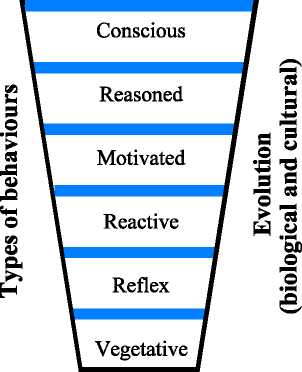

model them. Figure 1 shows a diagram of the types of

behaviours described above.

Figure 1. Abstraction levels in animal behaviour

(Gershenson, 2001).

We believe that the behaviours in the higher levels

evolved and developed from the behaviours in the

lower levels, since in animals you cannot find higher

levels of behaviour without the lower ones. Thus,

higher levels of behaviour require the lower ones, in a

similar way as children need to develop first lower

stages in order to reach higher ones (Piaget, 1968).

Also the higher types of behaviour in many cases can

be seen as complex variants of the lower ones.

Therefore, it is sensible to attempt to build artificial

cognitive systems exhibiting adaptive behaviour of

higher levels incrementally: in a bottom-up fashion

(Gershenson, 2001:3). This does not mean that we

cannot model any level separately. But the more levels

we consider, the less-incomplete our models will be.

Historically, KBS were used first trying to model

and simulate the intelligence found at the level of

reasoned behaviours in a synthetic way (Steels, 1995;

Verschure, 1998; Castelfranchi, 1998). This means that

we build an artificial system in order to test our model,

instead of contrasting our model directly with

observations on the modelled system. The synthetic

method allows us to contrast our theories with artificial

systems, and in the case of intelligence and mind,

theories are very hard to contrast with the natural

systems. KBS have proven to be acceptable models of

the processes of reasoned behaviours. Not only they

help us understand reasoned behaviours, but are able

to simulate these behaviours themselves. But when

people tried to model the lower levels ofbehaviour, the

artificial systems which were built failed to reproduce

the behaviour observed in natural systems, mainly

animals (Brooks, 1995). This was one of the strong

reasons that motivated the development of BBS on the

first place, but the fact is that BBS have modelled

acceptably animal adaptive behaviour. BBS help us

understand adaptive behaviour (e.g. Webb, 1996;

2001), but also we can build artificial systems which

show this adaptiveness (Maes, 1991).

Observed reality

Adaptive

Behaviourj

Cognitive

Processes

Natural

Exhibitions of

Intelligence

Synthetic theories

KBS

BBS

I Computer

JK. ∖ Simulations of

'"⅛ Intelligence

Figure 2. Simulating exhibitions of intelligence

(Gershenson, 2001).

But if we believe that reasoned behaviours evolved

and developed from lower levels of behaviour, we

More intriguing information

1. ‘I’m so much more myself now, coming back to work’ - working class mothers, paid work and childcare.2. DURABLE CONSUMPTION AS A STATUS GOOD: A STUDY OF NEOCLASSICAL CASES

3. The name is absent

4. The name is absent

5. A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON UNDERINVESTMENT IN AGRICULTURAL R&D

6. The name is absent

7. Deletion of a mycobacterial gene encoding a reductase leads to an altered cell wall containing β-oxo-mycolic acid analogues, and the accumulation of long-chain ketones related to mycolic acids

8. The name is absent

9. The Impact of Minimum Wages on Wage Inequality and Employment in the Formal and Informal Sector in Costa Rica

10. Tariff Escalation and Invasive Species Risk