Mirror System

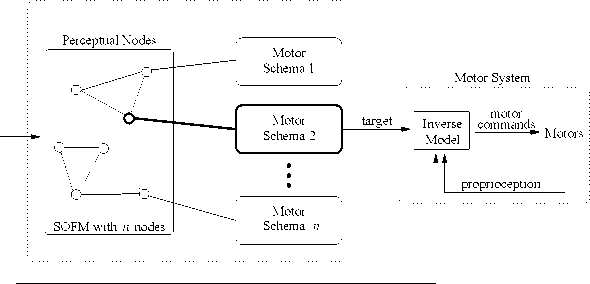

Figure 1: The architecture consists of (1) a mirror system, which is a coupling of perceptual and motor structures that

are built up from experience; and (2) a motor system, which consists of innate skills that can convert the output of the

mirror system into motor commands.

we are considering more complex relationships (e.g.

many-to-one).

2.1 Building the Mirror System

The structures that make up the mirror system

shown in Figure 1 are built up from experience, dur-

ing a learning phase. A temporal attention system is

used to categorise the perceptual input of the mirror

system into discrete perceptual structures, and each

perceptual structure is then associated directly to a

motor structure. The development of the mirror sys-

tem is therefore Perceptuo-Centrically driven, i.e. it

is built bottom-up through perceptual experience.

Perceptual Nodes

The perceptual categorisation is achieved using a

Self Organising Feature Map (SOFM), which is a

useful tool for modelling robotic sensory input (see

for example Nehmzow, 1999). The SOFM attempts

to cover the sensory input space with a network

of nodes, and edges connecting neighbouring nodes

determined by a Euclidean distance measure; it is

topology-preserving, i.e. a cluster of nodes repre-

sents a region in the sensory space. We are interested

in a variation of the SOFM, where structures (nodes

in the network) grow from experience as required,

rather than being specified a-priori.

We have adopted and suited to our purposes an al-

gorithm developed by Marsland et al. (2001), which

incorporates notions of habituation, novelty detec-

tion, and forgetting. Because of the growing, self-

organised nature of the system, it reflects at any one

time the current perceptual ‘memory’ of the agent,

and can easily adapt and accommodate new experi-

ences.

The attention system is described in detail in

(Marom et al., 2002), including a discussion of the

various parameters. Briefly, the algorithm involves

creating, modifying, and deleting nodes and edges in

response to on-line input, as follows:

• the sensory input is converted into a multi-

dimensional vector in the same space as the nodes

in the SOFM.

• the similarity of the input to all the existing nodes

is measured using a Euclidean distance measure,

and the closest node is referred to as the ‘winning’

node;

• if the input matches the winning node well (sig-

nalled through a novelty threshold), the winning

node and its neighbours habituate, and move to-

wards the input by a small fraction of the distance

to the input;

• otherwise the input is novel, so a new node is

created between the input and the winning node;

• if a node is completely habituated (signalled

through a full-habituation threshold), it is

‘frozen’: the node does not move from where it

is, and cannot be deleted; a forgetting mechanism

forces nodes to dishabituate at regular intervals,

and hence re-attend to their respective inputs;

• an edge is created between the winning node

and the second-best node, while other edges con-

nected to the winning node are aged; when an

edge is old enough it is deleted, and any discon-

nected nodes are deleted.

The system can thus handle novelty, avoid attending

to familiar stimuli, but adapt to changing stimuli.

The system is said to be attentive when nodes are

responding to stimuli, that is, when the nodes are

not all fully habituated. There are a number of pa-

rameters needed for the algorithm, but the most im-

portant one for the experiments in this paper is the

More intriguing information

1. The technological mediation of mathematics and its learning2. The name is absent

3. Improving behaviour classification consistency: a technique from biological taxonomy

4. The English Examining Boards: Their route from independence to government outsourcing agencies

5. The name is absent

6. Literary criticism as such can perhaps be called the art of rereading.

7. Review of “The Hesitant Hand: Taming Self-Interest in the History of Economic Ideas”

8. Innovation and business performance - a provisional multi-regional analysis

9. Kharaj and land proprietary right in the sixteenth century: An example of law and economics

10. Modelling Transport in an Interregional General Equilibrium Model with Externalities