Debussy: The Preludes 165

cisely the opposite direction, that is, toward the unreflec-

tive, the spontaneous, the involuntary and instinctive.

Hence, his predilection for childlike natures, for the dramas

of Maeterlinck, whose shadowy characters act less than

they are acted upon—by Fate. As Remy de Gourmont

says of them, “they can but suffer, smile, love; when they

try to understand, their troubled efforts give way to anguish

and their revolt fades into sobbing. They are climbing,

always climbing, the painful slopes of Calvary only to strike

their heads against an iron door”. In a word, it is the

“human” side of nature and the “natural” side of man

which particularly interest Debussy. And in this respect

he is thoroughly characteristic of his age and generation,

the generation of Bergson, that was brought up on Darwin,

Taine, Bernard and Renan.

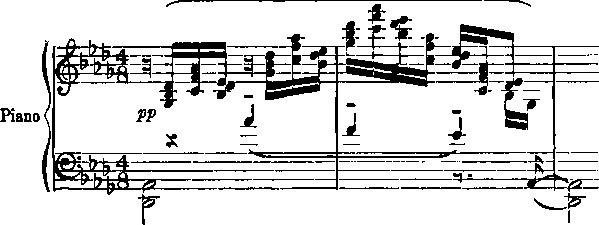

There are also illuminating analogies between certain

coloristic aspects of Debussy’s music and the technique of

impressionistic painting. Take, for example, the opening

measures of “Reflections in the Water”, where, by the use of

the sustaining pedal, Debussy has blended a whole series

of chords into one large, composite stretch of diaphanous

sonority. The procedure is quite characteristic of both his

piano music and the works for orchestra (where he secures

the same effect by glissandi on the harp, or by a subtle,

overlapping arrangement of the harmonies) and recalls

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. THE ECONOMICS OF COMPETITION IN HEALTH INSURANCE- THE IRISH CASE STUDY.

3. The name is absent

4. The name is absent

5. XML PUBLISHING SOLUTIONS FOR A COMPANY

6. Connectionism, Analogicity and Mental Content

7. The name is absent

8. ISO 9000 -- A MARKETING TOOL FOR U.S. AGRIBUSINESS

9. The name is absent

10. Towards Learning Affective Body Gesture