18

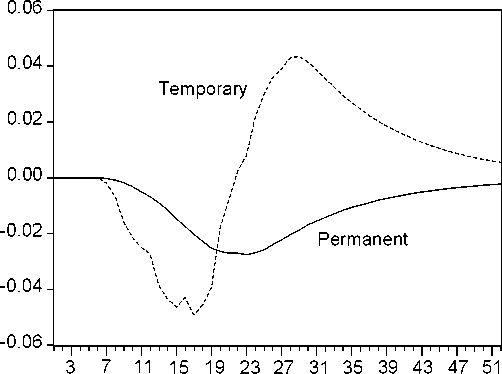

Figure 4.1. Temporary and permanent employment during a recession

(relative deviations compared to the levels in the reference case).

The patterns displayed in Figure 4.1 imply that the share of temporary work in total

employment falls slightly during the first half of the recession, whereas it rises markedly from

the trough to the end of recession. For the relatively “mild” recession considered here, the rise is

small, amounting to around 0.5 percent of total employment by the end of the recession. For a

sharper cyclical downturn, the effects are larger. Suppose that the recession is twice as deep,

with output 6 percent below the trend at the trough. The share of temporary work would then be

1.5 percentage points above the reference level at the end of the recession. These examples

suggest that the rise in temporary employment seen in Sweden can, at least in part, be accounted

for by the deep recession of the 1990s when the fall in GDP from peak to trough amounted to

roughly 10 percentage points.

How much of the rise in temporary work in Sweden can be explained by business cycle

factors and how much has to be attributed to a residual upward trend? A simulation with GDP

always on its trend path reveals a trend rise in the share of temporary work irrespective of

business cycle conditions. This “pure” trend rise amounts to around two percentage points if we

predicted with mean absolute errors of 0.6 percentage points. See Holmlund and Vejsiu (2001) for further details.

More intriguing information

1. Moffett and rhetoric2. The name is absent

3. RETAIL SALES: DO THEY MEAN REDUCED EXPENDITURES? GERMAN GROCERY EVIDENCE

4. The name is absent

5. Discourse Patterns in First Language Use at Hcme and Second Language Learning at School: an Ethnographic Approach

6. Human Resource Management Practices and Wage Dispersion in U.S. Establishments

7. The name is absent

8. The name is absent

9. Life is an Adventure! An agent-based reconciliation of narrative and scientific worldviews

10. On the job rotation problem