24

22

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

0.8

Country 1, Unemployment

0.4 0

τ (%)

Country 2, Unemployment

8

7.8

7.6

7.4

7.2

7

6.8

6.6

0.8

60

0.4 0

τ (%)

b1

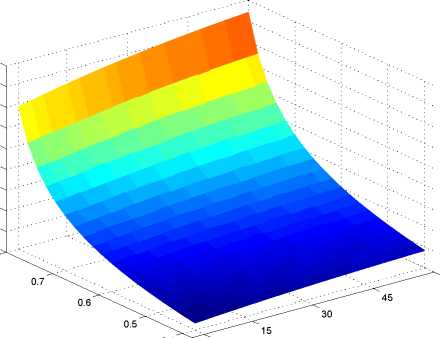

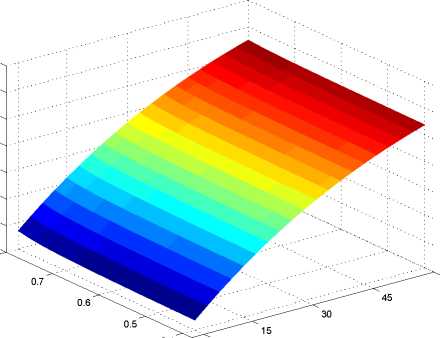

Figure 2: Country 1 labor market regulation and unemployment in countries 1 and 2

(=3). [Rate of unemployment on the vertical axis.]

constant returns to scale, and, most importantly, frictionless labor markets. The second

sector has heterogeneous firms, monopolistic competition, search frictions, and trade costs.

When trade costs fall, the second sector becomes more competitive, and workers leave

the no-unemployment num´eraire sector to fuel the expansion of the other sector. This

tends to result in higher aggregate unemployment. This result crucially depends on the

existence of the num´eraire sector. There is a second important difference relative to our

model: In most of their analysis, Helpman, Itskhoki, and Redding assume that preferences

are quasilinear such that all changes in income are absorbed by the homogeneous good.

This means that additional income due to gains from trade does not create additional

demand in the unemployment-ridden second sector and can, therefore, not compensate

the increase in unemployment.

Result 1b [Labor market reform]

If one country increases its unemployment benefits, then unemployment increases in that

country.

An increase of b1 from 0.4 to 0.8 (at the benchmark value of τ = 30%) drives up the rate

of unemployment from about 7% to about 20%. This result is in line with closed economy

search-and-matching models and with empirical evidence.23 We will study in detail below

how the geographical location of the country with the deteriorating institutions conditions

the unemployment effect. Figure 2, however, already clearly suggests that the gradient of

u1 with respect to b1 is smaller if country 1 is more open to international trade.

Result 1c [Institutional spill-overs]

If one country increases its unemployment benefits, then, in all other countries, unem-

ployment rises. While this qualitative pattern is very robust, the size of the spill-over

23 See Bassanini and Duval (2006).

20

More intriguing information

1. The Dynamic Cost of the Draft2. FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL SERVICE PROGRAMS AND FOREIGN RELATIONS

3. Wettbewerbs- und Industriepolitik - EU-Integration als Dritter Weg?

4. The name is absent

5. PERFORMANCE PREMISES FOR HUMAN RESOURCES FROM PUBLIC HEALTH ORGANIZATIONS IN ROMANIA

6. An institutional analysis of sasi laut in Maluku, Indonesia

7. Pursuit of Competitive Advantages for Entrepreneurship: Development of Enterprise as a Learning Organization. International and Russian Experience

8. TLRP: academic challenges for moral purposes

9. The name is absent

10. Cross-Country Evidence on the Link between the Level of Infrastructure and Capital Inflows