important, more capital-intensive industries. A gradual upgrading of skills can be deduced from

the increase of medium skill-intensive industries (plastics, paper, wood). CEECs also

strengthened their comparative advantage in the production of motor vehicles. Moreover, there

has been a strong rise in the output of the technology-driven electrical industry, which has more

than tripled since 1995.

References:

K. H. Midelfart-Knarvik, H. G. Overmann, S. J. Redding and A. J. Venables (2000), “The Location of European Industry”, Economic

Papers 142, prepared for the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Commission.

H. Handler (2003), ed., “Structural Reforms in the Candidate Countries and the European Union”, Austrian Ministry for Economic Affairs

and Labour, Economic Policy Section, Vienna.

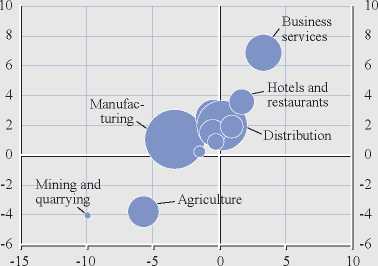

2.2 SECTORAL RE-ALLOCATION

Differences in specialisation patterns may be

reflecting the variation in the speed of structural

adjustment across EU countries or regions.

Indeed, structural adjustment has been a

continuous characteristic of the business cycles

over the last 15 years for the euro area (see

Chart 4). When accounting for employment

gains and losses during booms and recessions

in the two business cycle periods 1985-1993

and 1995-2000, the data indicate that there has

been a continuous increase in the relative

importance of the services sectors, while

manufacturing, agriculture and mining and

quarrying have lost weight in total employment.

This gives an indication as to the importance of

structural adjustments over the business cycle.

Finally, the comparison of the cycle 1987-1993

with 1993-200028 shows that sectoral re-

allocation has been a persistent feature of the

euro area for the last two decades, contrary to

the US experience where structural adjustment

was mainly a feature of the 1990s29.

28 Cycles have been determined on a trough-by-trough basis; for

the period 1993-2000 the small sub-cycles 1993-1997 and 1997-

1999 have been subsumed under one cycle encompassing the

entire period (see also section 3.1 where the cyclical behaviour

of euro area GDP is discussed in more detail).

29 See E. L. Groshen and S. Potter (2003) “Has Structural Change

Contributed to a Jobless Recovery”, Federal Reserve Bank of

New York, Vol. 9, no 8 for a comparison with cyclical and

structural job adjustments in the United States for the business

cycles in the early 1980s and the late 1990s.

Chart 4 Euro area business cycles and structural adjustment

1987-1993

Job growth in recovery (percent) (y-asis)

Job growth in recession (percent) (x-asis)

1993-2000

Job growth in recovery (percent) (y-asis)

Job growth in recession (percent) (x-asis)

10

-2

-4

Manufacturing

-6 j—

-10

Mining and

quarrying ∙

-5

10

Business

services

Distribution

— Hotels and

restaurants

4Agiiculture

-2

-4

- -6

10

Sources : Eurostat, NCBs, ECB calculations.

Note: The size of the circles refer to the average share of the sector in the euro area over the indicated period. Sector names have been added

only for selected sectors.

22

ECB

Occasional Paper No. 19

July 2004

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. Putting Globalization and Concentration in the Agri-food Sector into Context

3. Policy Formulation, Implementation and Feedback in EU Merger Control

4. Palkkaneuvottelut ja työmarkkinat Pohjoismaissa ja Euroopassa

5. The Role of Immigration in Sustaining the Social Security System: A Political Economy Approach

6. Tissue Tracking Imaging for Identifying the Origin of Idiopathic Ventricular Arrhythmias: A New Role of Cardiac Ultrasound in Electrophysiology

7. Before and After the Hartz Reforms: The Performance of Active Labour Market Policy in Germany

8. AN IMPROVED 2D OPTICAL FLOW SENSOR FOR MOTION SEGMENTATION

9. How do investors' expectations drive asset prices?

10. The name is absent