some countries could follow policies that maintain or even reduce explicit deficits and

debt levels while simultaneously increasing prospective deficits (the so-called “one-off”

measures). Such policies would alter the timing of deficit accruals but are unlikely to be

associated with any measurable regularity in real fiscal impulses.

The reason for drawing such a conclusion is that a particular time series of government

net cash flows may be associated with myriad ways of arranging the sizes and timing of

different taxes and expenditures - each of which may generate different expectations

among the public about whether they are temporary or permanent, and each of which

could be associated with different distributions of fiscal burdens among private agents

situated differently in their life-cycle stages. Hence, a particular time series of deficits and

debt may be associated with wildly different real underlying fiscal policies - that is, a

given time series may be associated with different real flows and distributions of

consumption, saving, investment, and output, and different levels of real interest rates,

inflation, and exchange rates. These differences in real economic outcomes would emerge

primarily because each distinct policy would exert differential effects on different

subgroups of individuals—distinguished, especially, with regard to their life-cycle stage.24

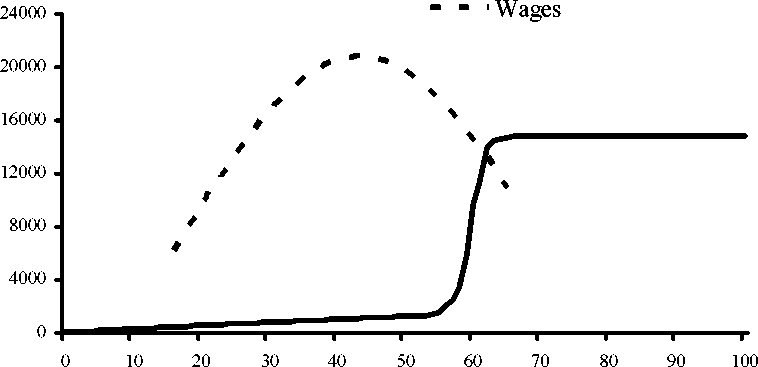

To provide a simple example, consider a strictly pay-as-you-go expansion of a public

pension program. Retiree benefits are increased immediately and permanently by €X each

year and those increases are financed by additional receipts of €X each year sourced from

workers’ payrolls. Figure 3.2 shows stylized profiles of public pension benefits and wage

earnings by age. Those profiles show that the policy of pay-as-you-go pension increases

would benefit older generations and the payroll tax increases would impose additional

financial burdens on younger workers. By construction, however, there would be no

change in the time series of the projected difference between total annual receipts and

outlays as a result of this policy change.

Figure 3.2 Social Security Benefit and Wage Profiles by Age

Euros/

Year

------Social Security Benefits

Age

For a related discussion see Gokhale (2004).

67

More intriguing information

1. Private tutoring at transition points in the English education system: its nature, extent and purpose2. Ronald Patterson, Violinist; Brooks Smith, Pianist

3. THE WAEA -- WHICH NICHE IN THE PROFESSION?

4. Reputations, Market Structure, and the Choice of Quality Assurance Systems in the Food Industry

5. Developmental Robots - A New Paradigm

6. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews

7. The name is absent

8. The name is absent

9. The name is absent

10. Foreword: Special Issue on Invasive Species