today to 5.0 million in 2070), and the number of working-age persons (15-64)

is reduced by 10 per cent from 2002 to 2040 and by 16 per cent from 2002 to

2080. Over the same two periods, the number of elderly citizens (65+) increases

by 52 per cent and 47 per cent, respectively. Consequently, the demographic

dependency ratio increases by 27 per cent from 2002 to 2040 and by 28 per

cent from 2002 to 2080, cf figure 1. This indicates that the increase in the

dependency ratio during the next 35 years is not a phenomenon that is isolated

to the echo effects of the large post-war generations. Rather, it is a permanent

shift to a higher level15.

5 Fiscal sustainability

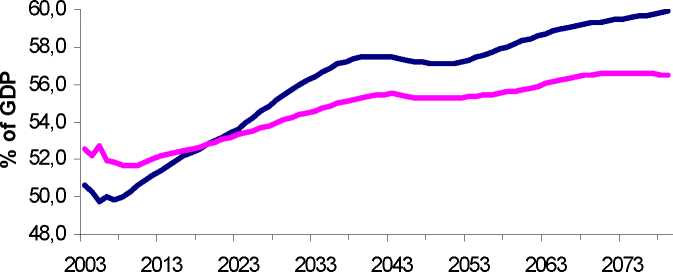

We start by presenting the path for public expenditures and revenues under un-

changed policies, cf figure 2. It is seen that expenditures gradually but steadily

increase to a level systematically above revenues16 .

Figure 2: Public expenditures and revenues

^—Expenditures---Revenues

Source: Velfærdskommissionen (2005d)

15 Compared to previous yet very recent demographic forecasts, the shift in the dependency

ratio is qualitatively different. In the 2001 forecast, the dependency ratio has a global peak

around 2040, but the ratio is then reduced to a level which is in b etween the current level and

the peak in 2040. This suggests that the demographic ageing problem has both a temporary

and a permanent component. The current demographic pro jection implies that the ageing

problem is almost entirely a permanent phenomenon, see e.g. Andersen et. al. (2005).

16Note that deposits into private pension funds are deductable in taxable income, the return

is taxed (at a low rate), but withdrawals are also taxable income. Since there has been a

substantial build-up of pension funds since the late 1980s this implies that there is a substantial

deferred tax payment in current pension funds. Therefore, the average tax share increases,

despite unchanged tax rates.

14

More intriguing information

1. The mental map of Dutch entrepreneurs. Changes in the subjective rating of locations in the Netherlands, 1983-1993-20032. Antidote Stocking at Hospitals in North Palestine

3. A Regional Core, Adjacent, Periphery Model for National Economic Geography Analysis

4. sycnoιogιcaι spaces

5. Deletion of a mycobacterial gene encoding a reductase leads to an altered cell wall containing β-oxo-mycolic acid analogues, and the accumulation of long-chain ketones related to mycolic acids

6. The name is absent

7. The name is absent

8. Problems of operationalizing the concept of a cost-of-living index

9. The name is absent

10. On the job rotation problem