What is going on? Why does a seemingly natural way of modelling (de)merit

good arguments lead to results whose intuitive appeal depends on the elasticity

of substitution? Let us consider the limiting case of Leontief preferences, and

ignore—for the sake of graphical representation—the standard non-numéraire good.

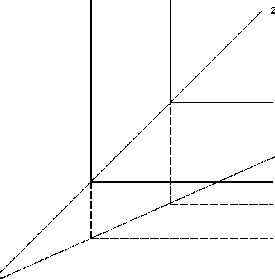

Suppose that a person’s preferences can be represented by min{z, y}.Thisperson

has L-shaped indifference curves with the corners lying on the 45o line, as shown

in figure 1.

Leontief preferences and a demerit good

The government, on the other hand, thinks of good y as a demerit good and

subscribes to the preference ordering represented by min{z, 1 y}. The associated

indifference curves are the dashed lines. Clearly, the government’s preferences

are more favourable to commodity y than the agent’s preferences are!

With Leontief preferences, no finite subsidy will be able to distort the agent’s

budget allocation away from the laissez-faire solution, but once the degree of sub-

stitutability becomes positive, it will. The reason why discounting a commodity

leads to subsidisation should now be clear. The government respects that red

wine is complementary to a pasta meal. But it regards one bottle of wine only

half as good as you do. In order to get the maximal utility out of a pasta dish,

it wants you to drink more wine, not less.

This paradox holds true more generally. Notice that the government’s MWP

for the (de)merit good (θЦ3(z, x, θy)) has the following elasticity w.r.t. θ:

dlog( 3 ) = 1 - (_∂log y(z,x, θy)

∂logθ I ∂ log(θy)

(10)

Thus, whether the government’s MWP exceeds or falls short of that of the con-

sumer depends on whether the (own) demand price elasticity for the (de)merit

good exceeds or falls short of 1 in absolute value. If the demand for tobacco, say,

is inelastic, the demand price elasticity is likely to be large, and under the scaling

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. Cyber-pharmacies and emerging concerns on marketing drugs Online

3. Mergers and the changing landscape of commercial banking (Part II)

4. The name is absent

5. Business Cycle Dynamics of a New Keynesian Overlapping Generations Model with Progressive Income Taxation

6. ISO 9000 -- A MARKETING TOOL FOR U.S. AGRIBUSINESS

7. Heterogeneity of Investors and Asset Pricing in a Risk-Value World

8. The name is absent

9. Mergers under endogenous minimum quality standard: a note

10. The name is absent