sufficiently high, for the environmental policy to have a very high chance of

being implemented.

A perhaps more interesting result is that by proposing a tax level below the

one required to bring the lake back to a socially optimal oligotrophic state, a

politician can ensure that he is elected. This shows that political ambition can

indeed prevent socially desirable policy from being implemented.

Appendices

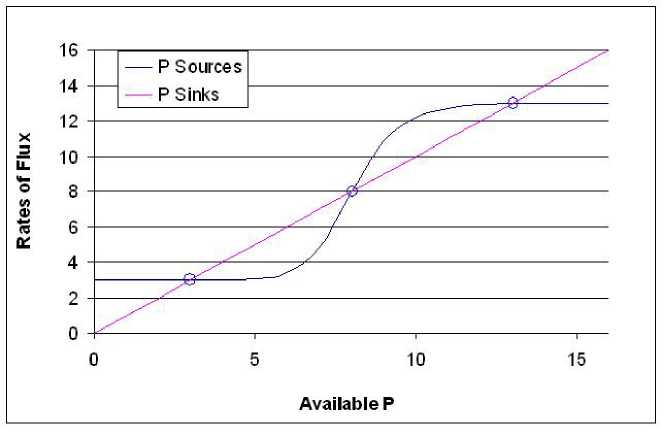

A Phosphorous Sources and Sinks

With the stock of phosphorous held constant, the phosphorous sink and source

equations can each be plotted as in Figure 5 and by Carpenter et al. (1999)

to show the rates of flux of phosphorous against the quantity of available P .

Superimposing the phosphorous sinks’ straight line and the phosphorous recy-

cling’s sigmoid shows the domains of attraction of oligotrophic and eutrophic

states. The upper point of instersection between the two curves is an attrac-

tor toward oligotrophy, whereas the lower intersection is an attractor toward

eutrophy. The intersection point in the middle is an unstable repeller and rep-

resents a Skiba point. This means that at this level of phosphorous stock, a

small change in the stock could precipitate the lake into either an oligotrophic

or eutrophic state. This illustrates the possible existence of a hysteresis in the

lake’s response to phosphorous input.

The graph illustrates that a eutrophied lake can be restored in several ways:

Figure 5: Phosphorous Sources and Sinks

• By increasing the sinks, i.e., by affecting s and thus altering the slope

of the ‘sinks’ line thereby changing the points of intersection with the

23

More intriguing information

1. SOCIOECONOMIC TRENDS CHANGING RURAL AMERICA2. IMPROVING THE UNIVERSITY'S PERFORMANCE IN PUBLIC POLICY EDUCATION

3. Business Networks and Performance: A Spatial Approach

4. 101 Proposals to reform the Stability and Growth Pact. Why so many? A Survey

5. Who is missing from higher education?

6. The mental map of Dutch entrepreneurs. Changes in the subjective rating of locations in the Netherlands, 1983-1993-2003

7. Output Effects of Agri-environmental Programs of the EU

8. The name is absent

9. Ronald Patterson, Violinist; Brooks Smith, Pianist

10. Should informal sector be subsidised?