became more and more wary about inward migration, which in turn

produced more pressure on politicians for "decisive" action in this area.

The important distinction between economic and forced migration often

threatened to be lost in the process. Although states are generally free to

decide on the number of economic migrants they are willing to accept, in

the area of forced migration international obligations such as the Geneva

Convention on the Status of Refugees impose important obligations on

states. However, this is not to dispute the fact that, with the door to legal

immigration shut in most states since the early 1970s, a significant

number of economic migrants have taken the 'asylum route' as it has often

constituted the only remaining avenue for third country nationals to

legally settle in one of the OECD countries. In the 1990s, asylum

applications therefore became a primary concern for policy makers in all

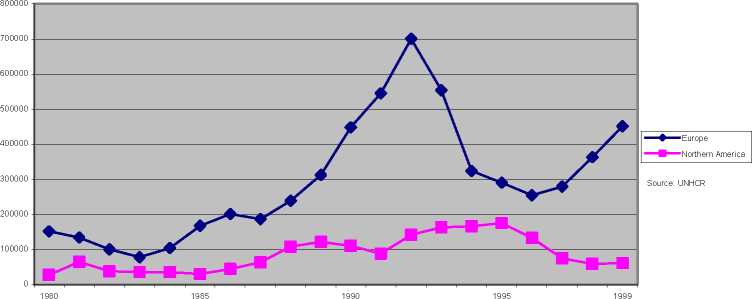

OECD states. Figure 1 shows that the number of asylum applications filed

in the developed world increased significantly in the late 1980s and early

1990.

Figure 1: Asylum Applications in Europe & North America, 1980-99

However, policy-makers are not just concerned about the growth in the

being swamped by a flood of fiddlers stretching our resources—and our patience—to

breaking point" (The Sun)'; "Hello Mr Sponger... Need Any Benefits?" (Daily Star,

26/04/2002). "Scandal of how it costs nearly as much to keep an asylum seeker as a room

at the Ritz" (The Mail); " . we resent the scroungers, beggars and crooks who are

prepared to cross every country in Europe to reach our generous benefits system" (The

Sun, 07/03/2001).

More intriguing information

1. Behavioural Characteristics and Financial Distress2. Demand Potential for Goat Meat in Southern States: Empirical Evidence from a Multi-State Goat Meat Consumer Survey

3. The name is absent

4. he Effect of Phosphorylation on the Electron Capture Dissociation of Peptide Ions

5. FOREIGN AGRICULTURAL SERVICE PROGRAMS AND FOREIGN RELATIONS

6. A model-free approach to delta hedging

7. The name is absent

8. The name is absent

9. The name is absent

10. Aktive Klienten - Aktive Politik? (Wie) Läßt sich dauerhafte Unabhängigkeit von Sozialhilfe erreichen? Ein Literaturbericht