27

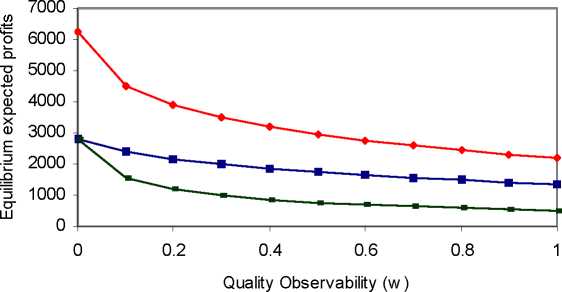

parameterization. Figure 3 also suggests that firms have an incentive to privatize their

reputations. For example, many food retailers sell products labeled with their own brand as

high quality products (Noelke and Caswell). The drawback of this strategy is that when a

problem occurs, the firms are identified with these brands and are clear targets in the

marketplace (Hennessy, Roosen, and Jensen).

—■— Reputation is a private good

« Monopoly

—— Reputation is a public good

Figure 3. Equilibrium responses of expected profits to changes in quality observability

(a=50, b=1, β=0.9)

It is not possible to state which situation yields higher welfare in general. Processors

would prefer, as expected, to be the only market participants and for reputations to be private

rather than public goods. It is also clear from Figure 4 that consumers prefer the scenario of a

duopoly with private reputations to that of a monopoly with collective reputations. However,

consumers’ choice between monopoly and duopoly with public reputations depends on the

level of quality observability, and the relevant discount factor. 15 In short, we can only say that

the duopoly situation with collective reputations is Pareto dominated by the other duopoly

scenario considered.16 This discussion provides support for some of the policies proposed by

Hennessy, Roosen, and Jensen to overcome some causes of systemic risk in the food industry.

The authors advocate for strategies such as improving traceability, testing, mandated labeling,

More intriguing information

1. Fiscal Sustainability Across Government Tiers2. The name is absent

3. Behavior-Based Early Language Development on a Humanoid Robot

4. The Advantage of Cooperatives under Asymmetric Cost Information

5. Wettbewerbs- und Industriepolitik - EU-Integration als Dritter Weg?

6. The name is absent

7. Studying How E-Markets Evaluation Can Enhance Trust in Virtual Business Communities

8. The name is absent

9. Bridging Micro- and Macro-Analyses of the EU Sugar Program: Methods and Insights

10. Monetary Discretion, Pricing Complementarity and Dynamic Multiple Equilibria