25

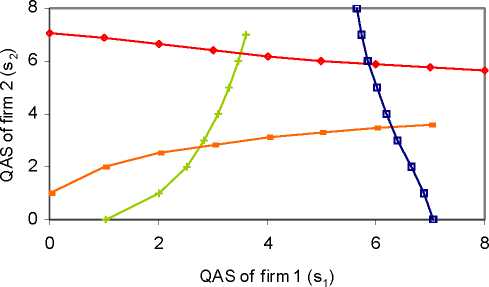

Figure 1. Best-response functions of firms (a = 50, b = 1, ω= 0.5 , β= 0.9)

outlasting the rival and capturing the entire market. But when a processor anticipates its rival

will invest heavily in quality assurance (and will become harder to outlast), the best the firm

can do is to reduce its own expenses and try to capture a higher per-period duopoly profit.

Comparing the stringency of assurance across the different types of reputation, Figure

1 reveals that, as expected, the equilibrium investments in QASs are lower when reputation is

a public good. When firms do not capture the full returns from their QASs, they will under-

invest in quality and try to free ride on other firms’ investments. Branding for example, could

be seen as an effort to convert reputations into a private good and hence capture a higher share

of the returns to investments in QASs.12 Economic theory predicts that if branding allows

processors to capture the returns to their investments, it will result in higher levels of quality

assurance. Also, though costlier QASs result in lower per-period outputs, the expected total

production (and hence consumption) is higher when reputation is a private good. This is driven

by the fact that more stringent controls result in a longer duopoly stage (in addition to any

output produced during the later monopoly periods).13

Results (not shown, but see footnote 13) indicate that monopoly total output levels are

higher than under duopoly when reputations are public in nature but not when reputations are

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The name is absent

3. GOVERNANÇA E MECANISMOS DE CONTROLE SOCIAL EM REDES ORGANIZACIONAIS

4. Does Competition Increase Economic Efficiency in Swedish County Councils?

5. The ultimate determinants of central bank independence

6. Regional dynamics in mountain areas and the need for integrated policies

7. AJAE Appendix: Willingness to Pay Versus Expected Consumption Value in Vickrey Auctions for New Experience Goods

8. The name is absent

9. An Interview with Thomas J. Sargent

10. The name is absent