28

and interpreting policies on mergers more leniently for the food industry. Our results suggest

that market concentration and/or identification of firms producing a given unit of output may

result in higher overall welfare.

-----Reputation is a public good

• Monopoly

—■— Reputation is a private good

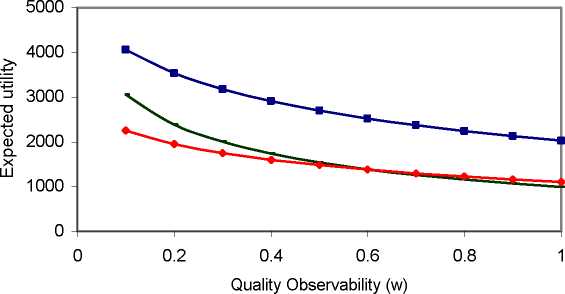

Figure 4. Equilibrium expected utility for the three scenarios considered for different

levels of quality observability (a = 50, b = 1, β= 0.9)

Conclusions

There exists a great disparity in existing QASs concerning the degree of stringency (and

associated costs) of the systems employed. We provide a rationale for those differences based

on market structure, the nature of the reputation mechanisms, and the size of the markets or

strength in demand for value-added products and whether the sought-after attributes are

credence, experience, or a mixture of both. We argue that QASs can be seen as efforts made by

firms to position themselves strategically in a marketplace where consumers can differentiate

between firms that deliver quality goods and those that deliver substandard quality.

Three models are developed to accommodate the different scenarios (monopoly,

duopoly with collective reputations, and duopoly with private reputations), and predictions are

obtained through comparative statics and numerical simulations. The later are performed under

the widely used assumptions of linear demands and constant marginal costs.

More intriguing information

1. Economie de l’entrepreneur faits et théories (The economics of entrepreneur facts and theories)2. Flatliners: Ideology and Rational Learning in the Diffusion of the Flat Tax

3. Orientation discrimination in WS 2

4. The name is absent

5. The name is absent

6. Developing vocational practice in the jewelry sector through the incubation of a new ‘project-object’

7. Urban Green Space Policies: Performance and Success Conditions in European Cities

8. Has Competition in the Japanese Banking Sector Improved?

9. Evolution of cognitive function via redeployment of brain areas

10. Eigentumsrechtliche Dezentralisierung und institutioneller Wettbewerb