Provided by Cognitive Sciences ePrint Archive

A Rational Analysis of Alternating Search and

Reflection Strategies in Problem Solving

Niels Taatgen ([email protected])

Cognitive Science and Engineering, University of Groningen

Grote Kruisstraat 2/1, 9712 TS Groningen, the Netherlands

Abstract

In this paper two approaches to problem solving, search and

reflection, are discussed, and combined in two models, both

based on rational analysis (Anderson, 1990). The first model is

a dynamic growth model, which shows that alternating search

and reflection is a rational strategy. The second model is a

model in ACT-R, which can discover and revise strategies to

solve simple problems. Both models exhibit the explore-

insight pattern normally attributed to insight problem solving.

Search vs. Insight

The traditional approach of problem solving is one of prob-

lem space search (see for example Newell & Simon, 1972).

Solving a problem means no more or less than finding an

appropriate sequence of operators, that transform a certain

initial state into a state that satisfies some goal criterium.

Problem solving is difficult if the sequence needed is long, if

there are many possible operators, or if there is no or little

knowledge on how to choose the right operator.

A different approach to problem solving is that the crucial

process is insight instead of search. This view also has a rich

tradition, rooted in Gestalt psychology. According to the

insight theory, the interesting moment in problem solving is

when the subject suddenly “sees” the solution, in a moment

when an “unconscious leap in thinking” takes place. Instead

of gradually approaching the goal, the solution is reached in

a single step, and reasoning efforts before this step have no

clear relation to it. In this sense problem solving is often

divided into four stages: exploration, impasse, insight and

execution.

Insight can be viewed in two ways: as a special process, or

as a result of ordinary perception, recognition and learning

processes (Davidson, 1995). Despite the intuitive appeal of a

special process, the latter view is more consistent with the

modern information-processing paradigm of cognitive psy-

chology, and much more open to both empirical study and

computational modeling.

Both the search and the insight theory select the problems

to be studied in accordance with their own view. Typical

“search”-problems involve finding long strings of clearly

defined operators, as in the eight puzzle, the towers-of-hanoi

task and other puzzles, often adapted from artificial intelli-

gence toy domains. “Insight”-problems on the other hand,

can be solved in only a few steps, often only one. Possible

operations are often defined unclearly, or misleadingly, or

are not defined at all. A typical insight problem is the nine-

dots problem, in which nine dots in a 3x3 array must all be

connected using four connected lines. The crucial insight is

the fact that the lines may be extended outside the 3x3

boundary. Other insight problems are the box-candle prob-

lem and several types of matchstick problems (see for exam-

ple Mayer, 1995). Due to this choice of problems, both

evidence from insight and search experiments tend to sup-

port their respective theories. Both theories ignore aspects of

problem solving. The search theory seems to assume that

subjects create clear-cut operators based on instructions

alone, and that subjects do not reflect on their own problem-

solving behavior, while the insight theory assumes all pro-

cessing that happens before the “insight” occurs has hardly

any relevance at all. So probably search and insight are both

aspects of problem solving, and the real task is to find a the-

ory of problem solving that combines the two (Ohlsson,

1984). One such view sees insight as a representational

change. Search is needed to explore the current representa-

tion of the problem, and insight is needed if the current rep-

resentation appears not to be sufficient to solve the problem.

In this view, search and insight correspond to what Norman

(1993) calls experiential and reflective cognition. If someone

is in experiential mode, behavior is largely determined by the

task at hand and the task-specific knowledge the person

already has. In reflective mode on the other hand, compari-

sons between problems are made, possibly relevant knowl-

edge is retrieved from memory, and new hypotheses are

created. If reflection is successful, new task-specific knowl-

edge is gained, which may be more general and on a higher

level than the existing knowledge.

The scheduling task

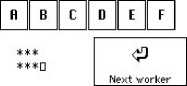

An example of a task in which both search and insight are

necessary is scheduling. Figure 1 shows an example of a

scheduling task used in our experiments. The goal is to

assign a number of tasks (6 in the example) to a number of

workers (2 in the example), satisfying a number of order

constraints. A solution to the example in figure 1 is to assign

Problem

There are 2 workers with

each 6 hours

Task A takes 1 hour

Task B takes 1 hours

Task C takes 2 hours

Task D takes 2 hours

Task E takes 3 hours

Task F takes 3 hours

The schedule has to satisfy

the following constraints:

Task C must be before A

Task E must be before B

Task F must be before B

Task D must be before C

Readq

Clear

Correct!

Figure 1: Example of a scheduling experiment

More intriguing information

1. DEVELOPING COLLABORATION IN RURAL POLICY: LESSONS FROM A STATE RURAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL2. Placenta ingestion by rats enhances y- and n-opioid antinociception, but suppresses A-opioid antinociception

3. The name is absent

4. The name is absent

5. Gerontocracy in Motion? – European Cross-Country Evidence on the Labor Market Consequences of Population Ageing

6. Electricity output in Spain: Economic analysis of the activity after liberalization

7. FDI Implications of Recent European Court of Justice Decision on Corporation Tax Matters

8. ADJUSTMENT TO GLOBALISATION: A STUDY OF THE FOOTWEAR INDUSTRY IN EUROPE

9. Credit Markets and the Propagation of Monetary Policy Shocks

10. Telecommuting and environmental policy - lessons from the Ecommute program