How does an infant acquire the ability of

joint attention?: A Constructive Approach

Yukie Nagai* Koh Hosoda*t Minoru Asada*t

* Dept. of Adaptive Machine Systems,

tHANDAI Frontier Research Center,

Graduate School of Engineering, Osaka University

2-1 Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka, 565-0871 Japan

[email protected], {hosoda, asada}@ams.eng.osaka-u.ac.jp

Abstract

This study argues how a human infant ac-

quires the ability of joint attention through

interactions with its caregiver from the view-

point of a constructive approach. This pa-

per presents a constructive model by which a

robot acquires a sensorimotor coordination for

joint attention based on visual attention and

learning with self-evaluation. Since visual at-

tention does not always correspond to joint at-

tention, the robot may have incorrect learning

situations for joint attention as well as correct

ones. However, the robot is expected to sta-

tistically lose the data of the incorrect ones

as outliers through the learning, and conse-

quently acquires the appropriate sensorimo-

tor coordination for joint attention even if the

environment is not controlled nor the care-

giver provides any task evaluation. The ex-

perimental results suggest that the proposed

model could explain the developmental mech-

anism of the infant’s joint attention because

the learning process of the robot’s joint at-

tention can be regarded as equivalent to the

developmental process of the infant’s one.

1. Introduction

A human infant acquires various and complicated

cognitive functions through interactions with its en-

vironment during the first few years. However,

the cognitive developmental process of the infant is

not completely revealed. A number of researchers

(Bremner, 1994, Elman et al., 1996, Johnson, 1997)

in cognitive science and neuroscience have attempted

to understand the infant’s development. Their be-

havioral approaches have explained the phenomena

of the infant’s development, however its mechanisms

are not clear. In contrast, constructive approaches

have potential to reveal the cognitive developmental

mechanisms of the infant. It is suggested in robotics

that the building of a human-like intelligent robot

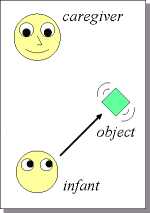

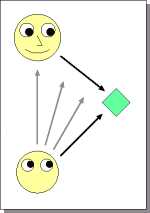

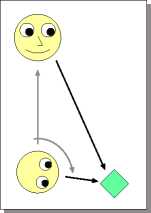

(a) 6th month (b) 12th month (c) 18th month

Figure 1: Development of infant’s joint attention

based on the insight of the infant could lead us to the

understanding of the mechanisms of the infant’s de-

velopment (Brooks et al., 1998, Asada et al., 2001).

Joint attention with a caregiver is one of the

abilities that help the infant to develop its so-

cial cognitive functions (Scaife and Bruner, 1975,

Moore and Dunham, 1995). It is defined as a pro-

cess that the infant attends to an object which the

caregiver attends to. Owing to the ability of joint

attention, the infant learns other kinds of social func-

tions, e.g. language communication, mind reading

(Baron-Cohen, 1995), and so on. On the basis of the

insight, robotics researchers have attempted to build

the mechanisms of joint attention for their robots

(Breazeal and Scassellati, 2000, Scassellati, 2002,

Kozima and Yano, 2001, Imai et al., 2001). How-

ever, their mechanisms of joint attention were

fully-developed by the designers in advance, and it

was not argued how the robot can acquire such an

ability of joint attention through interactions with

its environment.

Butterworth and Jarrett (1991) suggested that the

infant develops the ability of joint attention in three

stages: ecological, geometric, and representational

stages. In the first stage, the infant at the 6th month

has a tendency to attend to an interesting object in