Downloaded from rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org on July 20, 2010

Reaction beats intention A. E. Welchman et al. 5

(b)

phase 1 execution time total execution time

move

movement condition

movement condition

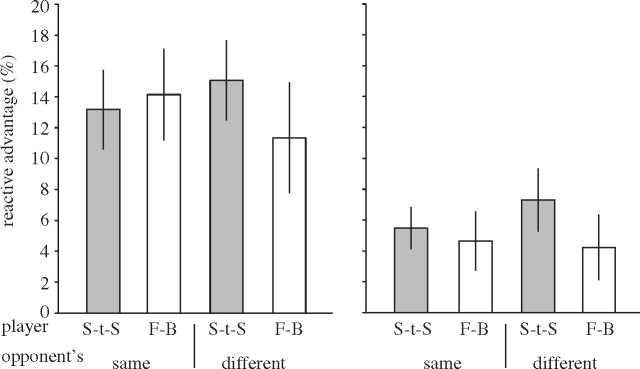

Figure 3. (a) Aerial view illustrating the set-up used in experiment 2. The row of buttons could be placed horizontally (illus-

trated for player 1 who would make a side-to-side movement, white bars) or vertically (illustrated for player 2 who would make

a front-back movement, grey bars). The two players could make the same type of movement (as in experiment 1) or a different

type of movement (as illustrated in the cartoon). (b) The reactive advantage (expressed as a percentage) for phase 1 and total

execution times in experiment 2. Data illustrate the between-subjects mean response with error bars showing s.e.m. Data from

the four different movement conditions are shown.

activated similarly when a participant performs an action

or observes the same movement performed by another

actor (Gallese et al. 1996; Iacoboni et al. 2005), poten-

tially priming movement production circuits and

facilitating the participant’s own actions. Behaviourally,

movement production can be influenced by viewing an

action that is either incongruent with one’s own (Brass

et al. 2000) or a transformed version of what one has to

perform (Craighero et al. 2002).

To investigate the possibility that the opponent’s move-

ment facilitates movement production, we tested whether

the direction in which participants moved influenced the

advantage for reactive movements. In particular, partici-

pants performed the three-button press sequence when

the buttons were configured for side-to-side or front -

back movements (figure 3a). Thus, a player could see

their opponent making a comparable movement that

could act as a model for their own movement (e.g. both

players make a front - back movement), or movement

orthogonal to their own action that would be of less use

in priming action preparation (e.g. one player moves

front - back while the other moves side-to-side). Consist-

ent with our previous experiments, we observed a

significant decrease in execution times for reactive move-

ments (F1,8 ¼ 11.484, p ¼ 0.01). However, there was no

significant effect of viewing a different movement from

one’s own (F1,8 ¼ 3.273, p ¼ 0.108) or any significant

interactions (figure 3b). Thus, the reactive advantage

does not appear to be modulated by viewing the opponent

making similar or dissimilar movements.

(c) Experiment 3

In our final experiment, we tested whether the social con-

text within which the participants found themselves might

be responsible for their facilitated reactive movements.

Previous work suggests differential performance when

humans believe they are interacting with another human

compared with a non-human agent such as a computer,

based on the notion that the mirror neuron system acts to

determine the intentions of others (Kilner et al. 2003;

Stanley et al. 2007; Gowen et al. 2008). To examine the

role that might be played by cortical systems responsible

for encoding the intentions of others, we contrasted

performance when participants competed against another

human (‘Person’ condition) or a computer on whose

display movements were presented symbolically. In

computer opponent conditions, participants were informed

either (i) that they were competing against a computer

(‘computer’ condition), or (ii) that they were competing

against another human located in a different testing room,

interfaced through the computer (‘virtual’ condition). In

actuality, the distribution of movement onset and move-

ment execution times produced by the computer was

determined from data previously recorded from the partici-

pant, meaning that they were playing against a historical

version of themselves, and thus involved in a demanding

competition. Debriefing participants at the end of the

session revealed this manipulation to have been successful,

with only one participant expressing doubts about the

authenticity of their computer-interfaced human opponent.

Consistent with the previous experiments, faster move-

ments were observed under reactive conditions (F1,9 ¼

26.689, p ¼ 0.001). However, the type of opponent

faced by participants (human, computer, virtual

human) neither had significant influence on execution

times (F2,18 ¼ 2.967, p ¼ 0.077) nor was the interaction

between the reactive advantage and the type of opponent

significant (F2,18 ¼ 1.650, p ¼ 0.220). The statistical

analysis on the type of opponent might suggest a marginal

effect. Nevertheless, inspecting the data (figure 4) does

Proc. R. Soc. B

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. GOVERNANÇA E MECANISMOS DE CONTROLE SOCIAL EM REDES ORGANIZACIONAIS

3. REVITALIZING FAMILY FARM AGRICULTURE

4. Spectral calibration of exponential Lévy Models [1]

5. The name is absent

6. The Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke

7. STIMULATING COOPERATION AMONG FARMERS IN A POST-SOCIALIST ECONOMY: LESSONS FROM A PUBLIC-PRIVATE MARKETING PARTNERSHIP IN POLAND

8. The Tangible Contribution of R&D Spending Foreign-Owned Plants to a Host Region: a Plant Level Study of the Irish Manufacturing Sector (1980-1996)

9. Government spending composition, technical change and wage inequality

10. The name is absent