Journal of Vision (2007) 7(8):1, 1-12

O 50

w

eŋ

a) Test LM

- CVH

• AJS

PDJ

25

0.125 0.5

Schofield, Ledgeway, & Hutchinson

Test spatial frequency (c∕deg)

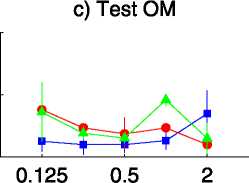

Figure 4. Sensitivity to motion contrast in test. Circles, squares, and triangles represent data for observers A.J.S., C.V.H., and P.D.J.,

respectively. Error bars are as described in Figure 1.

frequency. Adaptation to LM also induced an aftereffect

(CPSE , 40%) onto OM tests (Figure 3c, LM:OM),

although, in the case of P.D.J., this was very weak. The

effect was much less well tuned for spatial frequency than

either the LM:LM or the LM:CM interaction.

Adaptation to CM induced a moderate aftereffect

(CPSE , 50%) in CM tests (Figure 3e, CM:CM). This

effect was reasonably well tuned for spatial frequency, but

this tuning was broader than that found in the LM:LM

case. Although the effect peaked at 1 c/deg (+1 octave) for

two of three observers, the tuning was asymmetric for at

least one of these observers, suggesting that their peak

may have been poorly estimated. However, we cannot rule

out the possibility that the adaptable CM channels are

more widely spaced than those for LM and that we

adapted to one side of the center frequency of the nearest

channel for two of our three observers. Adaptation to CM

induced a moderate aftereffect (CPSE , 40%) onto OM

tests (Figure 3f, CM:OM). This effect showed some

spatial-frequency tuning. Adaptation to CM induced only

a very weak shift in PSE for LM tests (Figure 3d, CM:

LM). With the exception of one point (2 c/deg for A.J.S.),

the PSE did not exceed a motion contrast of 20%. This

very small effect was clearly not tuned for spatial

frequency.

Adaptation to OM induced a moderate aftereffect

(CPSE , 50%) onto OM tests (Figure 3i, OM:OM). The

effect was, at best, very broadly tuned and possibly low pass.

Adaptation to OM induced only very weak and broadly

tuned aftereffects (CPSE e 20%) onto CM (Figure 3h, OM:

CM) and LM (Figure 3g, OM:LM) tests.

We also assessed observer sensitivity to our test cues by

extracting just-noticeable differences (75% correct thresh-

olds) from the logistic fits for the control conditions where

observers adapted to the carrier only. These data (shown

in Figure 4) confirm that observers were quite sensitive to

changes in motion contrast.

We estimated the transfer of adaptation between cues

for each observer. The percentage transfer (T) was

calculated from the equation T = 100 (x/w), where x is

the between-cue PSE at 0.5 c/deg and w is the within-cue

PSE at 0.5 c/deg for the adapter. We used the central PSE

rather than those for all spatial frequencies as otherwise

estimated transfer was very sensitive to the relative tuning

of the aftereffects being compared. Table 1 shows the

estimated percentage transfers for each observer. These

results confirm the subjective impression gained from

inspecting Figure 3 that adaptation to an LM signal

transfers only partially to CM and OM tests, whereas

adaptation to CM transfers well to OM but only very

weakly to LM and adaptation to OM transfers only very

weakly to LM and CM.

Test (%)

|

Adaptation |

Observer |

LM |

CM |

OM |

|

LM |

C.V.H. |

44.33 |

66.77 | |

|

A.J.S. |

56.22 |

26.79 | ||

|

P.D.J. |

42.97 |

18.21 | ||

|

CM |

C.V.H. |

24.56 |

110.91 | |

|

A.J.S. |

31.34 |

64.48 | ||

|

P.D.J. |

29.28 |

100.61 | ||

|

OM |

C.V.H. |

1.44 |

27.16 | |

|

A.J.S. |

18.23 |

21.93 | ||

|

P.D.J. |

23.63 |

0 |

Table 1. Percentage transfer of adaptation between cues. See text

for details.

Discussion

We have characterized the spatial- and temporal-

frequency responses of human vision to moving OM

stimuli and compared these to sensitivities measured for

LM and CM under similar test conditions. OM sensitivity

curves are both spatially and temporally low pass, but OM

detection has reasonably high temporal acuity and, thus,

OM is unlikely to be a third-order cue as defined by Lu

and Sperling (2001). We have also tested the ability of

our motion cues to induce the dMAE onto patterns of a

similar type and assessed the degree to which the dMAE

More intriguing information

1. The name is absent2. The Structure Performance Hypothesis and The Efficient Structure Performance Hypothesis-Revisited: The Case of Agribusiness Commodity and Food Products Truck Carriers in the South

3. Declining Discount Rates: Evidence from the UK

4. Does South Africa Have the Potential and Capacity to Grow at 7 Per Cent?: A Labour Market Perspective

5. A novel selective 11b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitor prevents human adipogenesis

6. The name is absent

7. Popular Conceptions of Nationhood in Old and New European

8. Towards a Strategy for Improving Agricultural Inputs Markets in Africa

9. WP 48 - Population ageing in the Netherlands: Demographic and financial arguments for a balanced approach

10. The name is absent