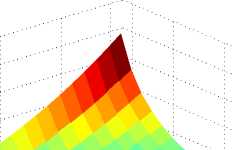

Country 1, ∆ Real wages

9"T

8-.

7-. .

6-. .

5

4

3

2

τ (%)

σ

10 60

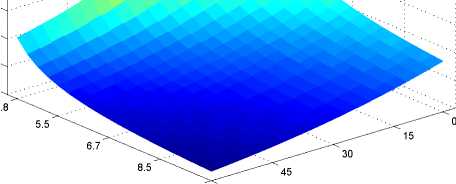

Country 2, ∆ Real wages

0-.

-0.5-. .

-1 - .

-1.5-. .

-2.5

10

30

15

45

3.8

0

σ

τ (%)

Figure A3: Change in real wages [on the vertical axis] as a function of trade costs and

the elasticity of substitution for a given change of b1 from 0.4 to 0.8.

country 1 is larger, home demand is more important, making it harder to spill-over bad

labor market institutions to foreign countries. However, for the foreign countries a larger

country 1 means a more important trading partner, leading to a higher sensitivity on the

economic performance of this country.

A2.3 The role of the elasticity of substitution and external economies

of scale

Result A3 [The elasticity of substitution and spill-overs]

The higher the elasticity of substitution, the smaller are the changes in real wages in all

countries following a rise of country 1’s unemployment benefits.

As discussed in the main text, an increase in the elasticity of substitution leads to a

weakening of the income effect and to a strengthening of the competitiveness effect and

thus lowers the spill-over effects of bad labor market institutions. As illustrated in Figure

A3 this implies that the wage drops in countries 2 and 3 become smaller.

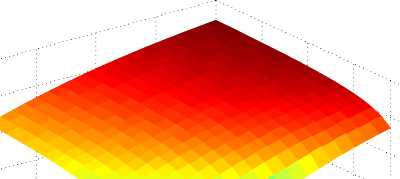

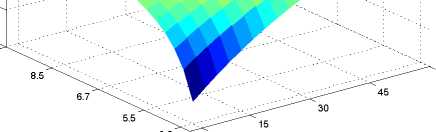

Result A4 [External economies of scale and spill-overs]

Stronger external economies of scale result in smaller decreases in real wages for all trading

partner countries. The results for country 1 are ambiguous.

The result is illustrated in Figure A4. For real wages, two things are important: the

nominal wage, and the price level for the aggregated final output good. Both, the nominal

wage and the price level for the aggregated final output good change the sign when ν varies.

For low ν’s the change is positive for both, whereas the change is negative for high ν’s.44

44Note that P1 = 1 due to our normalization. Hence, a decrease of P2 implies a higher relative price

53

More intriguing information

1. Job quality and labour market performance2. Volunteering and the Strategic Value of Ignorance

3. Optimal Tax Policy when Firms are Internationally Mobile

4. Industrial Cores and Peripheries in Brazil

5. The name is absent

6. Non Linear Contracting and Endogenous Buyer Power between Manufacturers and Retailers: Empirical Evidence on Food Retailing in France

7. The name is absent

8. What Lessons for Economic Development Can We Draw from the Champagne Fairs?

9. Public Debt Management in Brazil

10. The name is absent