й«Й 8 ' ®в® ' ≡ ' i ■■ ;■■■ ⅛≡ . ; ⅛ V à '■ : ⅛ , ;

ESSAYS ON ISSUES

THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

OF CHICAGO

DECEMBER 1991

NUMBER 52

Chicago Fed Letter

Personal bankruptcies

in retrospect

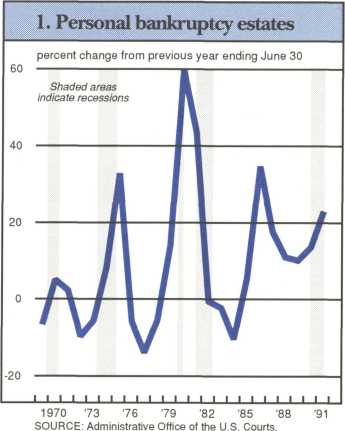

Most analysts consider the sustained

increase in personal bankruptcies

during the last seven years to be like a

snow storm in the middle of the sum-

mer: it should not have happened.

This is because, although personal

bankruptcies are historically cyclical,

rising during recessions as unemploy-

ment increases and declining during

expansions (see Figure 1), the increase

in personal bankruptcies after 1984

occurred during a period of extended

economic growth.

Many proposed explanations for why

personal bankruptcies increased dur-

ing a period of national economic

upswing assume that the upward trend

in the number of personal bankruptcy

filings during most of the 1980s was

countercyclical. However, an alterna-

tive explanation is that personal bank-

ruptcies responded to a series of local-

ized economic downturns which took

place during the 1980s. This conclu-

sion is consistent with the claim that

personal bankruptcies continued to

follow a cyclical pattern. This explana-

tion is supported by the fact that al-

though the longest peacetime expan-

sion in the history of the U.S. econo-

my occurred post-1982, these years

were also characterized by severe re-

gional economic shocks, which caused

personal bankruptcies to fluctuate

accordingly.

An analysis of personal bankruptcies

by state shows that, outside periods of

national economic recessions, increas-

es in personal bankruptcy filings dur-

ing the past decade were more ex-

treme in regions hit by negative eco-

nomic shocks. Although the down-

turns of the 1980s were contained

within specific regions of the country,

their consequences were very damag-

ing and often spilled over to different

sectors of the economy, causing a

more widespread financial distress.

The fact that personal bankruptcy

filings advanced also at the national

level during this period attests to the

severity of such localized recessions.

Moreover, the Bankruptcy Reform Act

of 1978, which made it easier to file for

bankruptcy, and an unprecedented

accumulation of household debt in

the 1980s somewhat exacerbated the

increase in personal bankruptcy filings

during these periods of localized eco-

nomic downturns.

1984-1986: the strain on farmers

and the oil price plunge

After increasing at the onset of the

1981-1982 recession, personal bank-

ruptcy filings declined, following their

cyclical pattern. The downward trend

was reversed, however, when personal

bankruptcies jumped 20% in 1985 and

32% in 1986 (see Figure 2). The in-

creases appeared to be countercyclical

since, by 1985, the civilian unemploy-

ment rate had fallen to approximately

7% from double-digit rates in 1982,

and the real economy was growing at

an annual rate of 3.4%. Despite the

general climate of well-being, two

major economic shocks took place

during the 1984-1986 period: farmers

experienced deep and prolonged

financial problems, and the 1986

plunge in oil prices led to a recession

in the Oil Patch states.

These localized economic disturbanc-

es forced a number of firms in the

affected sectors of the economy to

reduce both output and workers. As a

result, in 1986, the economy’s real

growth slowed to 2.7%, and employ-

ment in the goods-producing sector

fell by 300,000 jobs. Also, although

the national civilian unemployment

rate continued to fall, unemployment

rates in the states most affected by the

localized economic downturns in-

creased. Because personal bankrupt-

cies are sensitive to fluctuations in the

unemployment rate, as unemployment

increased in the distressed states, so

did the number of bankruptcy filings.

In the early 1980s, the agricultural

sector experienced severe financial

problems, mainly due to a decline in

U.S. farm exports. At the beginning of

1985, over 12% of all U.S. farms were

considered financially distressed by the

U.S. Department of Agriculture, with

60% of such farms concentrated in the

Corn Belt, the Great Lakes states, and

the Plains.1 Moreover, the adverse

effects of this difficult economic situa-

tion soon spilled over to agriculture-

related industries, creating a more

widespread economic disturbance.

In 1985, personal bankruptcies rose

20% at the national level. However,

increases were clearly more dramatic