Figure 5. The thick rectangle (left) represents the current view. View size is constant across all

magnification levels (middle). The same view at increasing scales shows more detail at the cost of less

context (right).

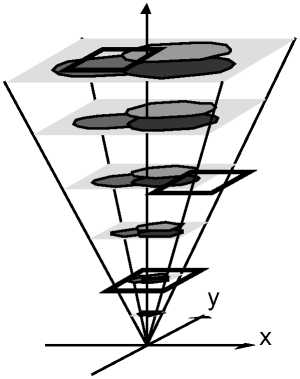

So far we have assumed that the content of the document is scale-independent. This is

unrealistic if we consider large ranges of scale. Consider geographical maps: depending on

their scale, they display varying levels of information. For example, a city will appear as a dot

and city name on a map of the whole country while the streets will be visible on a map of the

city. Objects in a multiscale document can be associated with a scale-range, so as to be

displayed only when the scale of the viewing window is within that range (Figure 6, left).

Some zoomable user interfaces, such as Pad (Perlin & Fox, 1993), Pad++ (Bederson &

Hollan, 1994) or Jazz (Bederson et al., 2000) automatically define the scale-range of each

object according to its size: when the view size of the object is smaller than a few pixels or

bigger than the view, it is faded out.

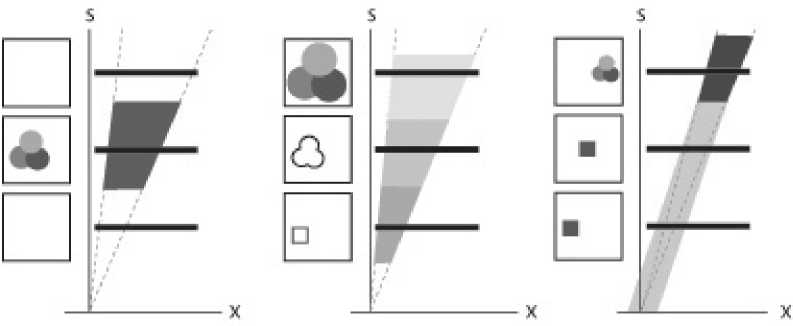

Scale ranges can also be used to implement semantic zooming (Perlin & Fox, 1993):

according to the viewing scale, a different object is shown (Figure 6, middle), e.g. a dot and

city name at small scale, and a street-map at higher scale. We use semantic zooming below to

represent the target of a pointing task as a fixed-size beacon at low scales, i.e. when the target

is smaller than a few pixels. The beacon is an object whose representation is independent of

the viewing scale (Figure 6, right).

More intriguing information

1. Modelling the health related benefits of environmental policies - a CGE analysis for the eu countries with gem-e32. Assessing Economic Complexity with Input-Output Based Measures

3. The name is absent

4. Quality practices, priorities and performance: an international study

5. The name is absent

6. The name is absent

7. The name is absent

8. Flatliners: Ideology and Rational Learning in the Diffusion of the Flat Tax

9. The name is absent

10. Do the Largest Firms Grow the Fastest? The Case of U.S. Dairies